Fenethylline

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

show

IUPAC name | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.015.983 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C18H23N5O2 |

| Molar mass | 341.415 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

show

SMILES | |

show

InChI | |

| | |

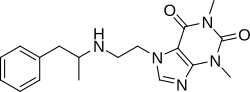

Fenethylline (BAN, USAN) is a codrug of amphetamine and theophylline that behaves as a prodrug to both of the aforementioned drugs. It is also spelled phenethylline and fenetylline (INN); other names for it are amphetamin

History[]

Fenethylline was first synthesized by the German Degussa AG in 1961 and used for around 25 years as a milder alternative to amphetamine and related compounds.[3] Although there are no FDA-approved indications for fenethylline, it was used in the treatment of "hyperkinetic children" (what would now be referred to as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) and, less commonly, for narcolepsy and depression. One of the main advantages of fenethylline was that it does not increase blood pressure to the same extent as an equivalent dose of amphetamine and so could be used in patients with cardiovascular conditions.[4]

Fenethylline was considered to have fewer side effects and less potential for abuse than amphetamine. Nevertheless, fenethylline was listed in 1981 as a schedule I controlled substance in the US, and it became illegal in most countries in 1986 after being listed by the World Health Organization for international scheduling under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances, even though the actual incidence of fenethylline abuse was quite low.[4][circular reference]

Pharmacology[]

The fenethylline molecule results when theophylline is covalently linked with amphetamine via an alkyl chain.[5]

Fenethylline is metabolized by the body to form two drugs, amphetamine (24.5% of oral dose) and theophylline (13.7% of oral dose), both of which are active stimulants. The physiological effects of fenethylline therefore seem to result from a combination of these two compounds,[6][7][8] although this is not entirely clear.[4]

Abuse and illegal trade[]

Abuse of fenethylline of the brand name Captagon is common in the Middle East,[9] and counterfeit versions of the drug continue to be available despite its illegality.[10][11] Captagon is much less common outside of the Middle East, to the point that police may not recognize the drug.

Many of these counterfeit "Captagon" tablets actually contain other amphetamine derivatives that are easier to produce, but are pressed and stamped to look like Captagon pills. Some counterfeit Captagon pills analysed do contain fenethylline however, indicating that illicit production of this drug continues to take place.[12] These illicit pills often contain "a mix of amphetamines, caffeine[,] and various fillers", which are sometimes referred to captagon with a lowercase C.

Fenethylline is a popular drug in Western Asia, and is allegedly used by militant groups in Syria.[13] It is manufactured locally by a cheap and simple process. In July 2019 in Lebanon, captagon was sold for $1.50 to $2.00 a pill.[14] In 2021 in Syria, low-quality pills were sold locally for less than $1, while high-quality pills are increasingly smuggled abroad and may cost upwards of $14 each in Saudi Arabia.[9]

According to some leaks, militant groups also export the drug in exchange for weapons and cash.[15][16] According to Abdelelah Mohammed Al-Sharif, secretary general of the National Committee for Narcotics Control and assistant director of Anti-Drug and Preventative Affairs, 40% of the drug users who fall in the 12–22 age group in Saudi Arabia are addicted to fenethylline.[17]

Increasing usage and seizures[]

According to UNODC, Saudi Arabia received seven tonnes of Captagon in 2010, a third of world supply.[18] In 2017, Captagon was the most popular recreational drug in the Arabian peninsula.[19]

On 26 October 2015, a member of the Saudi royal family, Prince Abdel Mohsen Bin Walid Bin Abdulaziz, and four others were detained in Beirut on charges of drug trafficking after airport security discovered two tons of Captagon (fenethylline) pills and some cocaine on a private jet scheduled to depart for the Saudi capital of Riyadh.[20][21][22] The following month, Agence France Press reported that the Turkish authorities had seized 2 tonnes of Captagon during raids in the Hatay region on the Syrian border. The pills, almost 11 million of them, had been produced in Syria and were being shipped to countries in the Arab states of the Persian Gulf.[23]

On 31 December 2015, the Lebanese Army announced that it had discovered two large scale drug production workshops in the north of the country. Large quantities of Captagon pills were seized. Two days earlier three tons of Captagon and hashish were seized at Beirut airport. The drugs were concealed in school desks being exported to Egypt.[24]

References to the drug were found on a mobile phone used by Mohamed Lahouaiej Bouhlel, a French-Tunisian who killed 84 civilians in Nice on Bastille Day, 2016.[25]

In May 2017, French customs at Charles de Gaulle airport seized 750,000 Captagon pills transported from Lebanon and destined for Saudi Arabia.[26] That year, two other separate discoveries of the pills were also made at Charles de Gaulle Airport in January, heading for the Czech Republic, and in February, hidden in steel moulds.[27] Further investigation showed that the seized products mainly contained a mixture of amphetamine and theophylline.[28]

In January 2018, Saudi Arabia seized 1.3 million Captagon pills at the Al-Haditha crossing near the border with Jordan.[29] In December 2018, Greece intercepted a Syrian ship sailing for Libya, carrying six tonnes of processed cannabis and 3 million Captagon pills.[30] In July 2019, a shipment of 33 million Captagon pills, weighing 5.25 tonnes, was seized in Greece coming from Syria.[31] Later that month, 800,000 Captagon pills were found on a boat in the United Arab Emirates.[32] In August 2019, Saudi customs at Al-Haditha seized 2,579,000 Captagon pills found inside a truck and a private vehicle.[33]

In February 2020, the UAE found 35 million Captagon pills in a shipment of electric cables from Syria to Jebel Ali.[34] In April 2020, Saudi Arabia seized 44.7 million Captagon pills smuggled from Syria,[35] and imposed an import ban on fruits and vegetables from Lebanon citing drug smuggling concerns, causing the price of Lebanese lettuce to plummet.[36][37] On 1 July 2020, an anti-drug operation coordinated in Italy by the Italian Guardia di Finanza and Customs and Monopolies Agency seized 14 tonnes of amphetamines, labeled as Captagon, smuggled from Syria and initially hypothesized by the Italian authorities to have been produced by ISIS,[38][39][40] which were found in three shipping containers filled with around 84 million pills, in the southern port of Salerno.[38][39][40][41] In November 2020, Egypt managed to seize two shipments of Captagon pills at Damietta port coming from Syria, the first had 3,251,500 tablets,[42] while the second contained 11 million tablets.[43] In December 2020, Italian authorities seized at Napoli about 14 tonnes of Captagon arriving from Latakia, Syria and heading towards Libya, including about 84 million pills, worth around $1 billion.[44]

In January 2021, Egyptian authorities seized eight tons of Captagon and another eight tons of Hashish at Port Said, from a shipment which arrived from Lebanon.[45] In February 2021, Lebanese customs seized at Beirut port a shipment of 5 million Captagon pills hidden in a tile-making machine, intended for Greece and Saudi Arabia.[46] In April 2021, Saudi authorities discovered 5.3m Captagon pills hidden in fruits imported from Lebanon.[47]

Production in Syria[]

The drug is playing a role in the Syrian Civil War.[48][49] The production and sale of fenethylline generates large revenues which are likely used to fund weapons, as well as combatants on different sides using the stimulant to keep them fighting.[49][50][51]

In May 2021, the UK newspaper The Guardian described the effects of Captagon production in Syria on the economy as a dirty business which is creating a near narco-state. Drug money flowing into Syria is destabilizing legitimate businesses, positioning it as the global epicentre of Captagon production, with increased industrialization, adaptation, and technical sophistication.[52] In June 2021, Saudi authorities at Jeddah port seized 14 million Captagon tablets hidden inside a shipment of iron plates coming from Lebanon.[53] In the same month, Saudi authorities seized a shipment of 4.5 million Captagon pills, smuggled inside several orange cartons, also at a Jeddah port.[54] In July 2021, Saudi customs discovered 2.1 million Captagon pills at Al-Haditha hidden in a tomato paste shipment.[55]

The New York Times reported in December 2021 that the Syrian Army's elite 4th Armoured Division, commanded by Maher al-Assad, oversees much of the production and distribution of Captagon, among other drugs. The unit controls manufacturing facilities, packing plants, and smuggling networks all across Syria (which have started to also move crystal meth).[9] The division's security bureau, headed by Maj. Gen. , provides protection for factories and along smuggling routes to the port city Latakia and to border crossings with Jordan and Lebanon. In the wake of sanctions against the Assad government, Jihad Yazigi, editor of The Syria Report, said captagon is now "Syria’s most important source of foreign currency".

See also[]

- Amfecloral

- Cafedrine

- Famprofazone

- Fencamine

- Theodrenaline

- ZDCM-04

References[]

- ^ Dictionary of Organic Compounds. CRC Press. 1996. pp. 3140–. ISBN 978-0-412-54090-5.

- ^ Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. January 2000. pp. 431–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- ^ Kristen G, Schaefer A, von Schlichtegroll A (June 1986). "Fenetylline: therapeutic use, misuse and/or abuse". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 17 (2–3): 259–71. doi:10.1016/0376-8716(86)90012-8. PMID 3743408.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Katselou M, Papoutsis I, Nikolaou P, Qammaz S, Spiliopoulou C, Athanaselis S (August 2016). "Fenethylline (Captagon) Abuse - Local Problems from an Old Drug Become Universal". Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 119 (2): 133–40. doi:10.1111/bcpt.12584. PMID 27004621.

- ^ Nickel B, et al. (1986). "Fenetylline: New results on pharmacology, metabolism and kinetics". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 17 (2–3): 235–257. doi:10.1016/0376-8716(86)90011-6. PMID 3743407.

- ^ Ellison, Theodore; Levy, Louis; Bolger, James W.; Okun, Ronald (1970). "The metabolic fate of 3H-fenethylline in man". European Journal of Pharmacology. 13 (1): 123–128. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(70)90192-5. PMID 5496920.

- ^ Alabdalla MA (September 2005). "Chemical characterization of counterfeit captagon tablets seized in Jordan". Forensic Science International. 152 (2–3): 185–8. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.08.004. PMID 15978343.

- ^ Wenthur CJ, Zhou B, Janda KD (August 2017). "Vaccine-driven pharmacodynamic dissection and mitigation of fenethylline psychoactivity". Nature. 548 (7668): 476–479. doi:10.1038/nature23464. PMC 5957549. PMID 28813419.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hubbar d, Ben; Saad, Hwaida (5 December 2021). "On Syria's Ruins, a Drug Empire Flourishes". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 8 December 2021 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ "2011 Global Assessment of Amphetamine-Type Stimulants" (PDF). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

- ^ "Why would the Islamic State group try to smuggle the 'drug of the Jihad' into Europe?". www.abc.net.au. 2 July 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ Alshehri AZA, Al Qahtani MS, Al Qahtani MA, Faeq AM, Aljohani J. Study of Adulterants and Diluents in Some Seized Captagon-Type Stimulants. Ann Clin Nutr. 2020; 3(1): 1017.

- ^ Todd B, McConnell D (21 November 2015). "Syria fighters may be fueled by amphetamines". CNN. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ^ Holley P (19 November 2015). "The tiny pill fueling Syria's war and turning fighters into superhuman soldiers". The Washington Post. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ^ Freeman C (12 January 2014). "Syria's civil war being fought with fighters high on drugs". The Telegraph. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- ^ Kalin S (12 January 2014). "Insight: War turns Syria into major amphetamines producer, consumer". Reuters. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ^ "40% of young Saudi drug addicts taking Captagon". Arab News. Jeddah. 28 October 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ^ "Insight - War turns Syria into major amphetamines producer, consumer". Reuters. 13 January 2014.

- ^ "A new drug of choice in the Gulf". The Economist. 18 July 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ Spencer R (26 October 2015). "Saudi prince held after seizure of two tonnes of amphetamines at Beirut airport". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ^ Baker G (26 October 2015). "Saudi prince arrested in Lebanon trying to smuggle two tonnes of amphetamine pills out of the country by private jet". The Independent. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ^ Vinograd C, Kassem M (26 October 2015). "Saudi Royal, Four Others Detained in Beirut Captagon Bust". NBC News. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ^ Agence France-Presse (20 November 2015). "Turkey seizes 11 million pills of 'Syria war drug': Reports". The Times of India. Istanbul. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- ^ The Daily Star (Lebanon): Tuesday raids in east Lebanon netted 800 kg of hash:police and Lebanese Army busts two drug factories

- ^ Sanchez R. "Attacker in Nice plotted for months with 'accomplices'". CNN. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ "In a first, authorities say they found 750,000 'Captagon' pills in France". The Washington Post. 30 May 2017.

- ^ "Customs seize 135 kg of captagon for first time in France". rfi.fr. 30 May 2017.

- ^ "Les 135 kilos de drogue saisis n'étaient pas du Captagon, "la drogue des djihadistes"". Le Parisien. 2017.

- ^ "Saudi customs bust drug smugglers with haul of 1.3m pills". Arab News. 12 January 2018.

- ^ Koutantou, Angeliki; Kambas, Michele; Stamp, David (14 December 2018). "Greece seizes big drugs haul from Syrian freighter sailing for Libya". Reuters. London. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ Georgiopoulos, George; Heinrich, Mark (5 July 2019). "Greece seizes record amount of amphetamine Captagon shipped from Syria". Reuters. London. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ "Dogs help seize 800,000 Captagon pills worth Dh3 million". Gulf News. 24 July 2019.

- ^ "Saudi officials stop Captagon smuggling plots". Arabian Business. 21 August 2019.

- ^ "Video: Massive drug bust in Dubai, 5.6 tonnes of captagon seized". Khaleej Times. 26 February 2020.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia busts drug smuggling operation from Assad's Syria". Middle East Monitor. 30 April 2020.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia bans fruit, vegetable imports from Lebanon". www.aa.com.tr. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ "Lebanese fear fruit and vegetables going to waste with Saudi market shut". Reuters. 12 May 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Del Porto, Dario; Foschini, Giuliano (1 July 2020). "Salerno, sequestrate 84 milioni di pasticche di droga dell'Isis: le stesse usate dai terroristi del Bataclan". La Repubblica (in Italian). Rome. Retrieved 21 July 2020.; Foschini, Giuliano (10 July 2020). ""La droga dell'Isis non-era dell'Isis": quelle 14 tonnellate di anfetamine sequestrate in Italia e il legame con la Siria di Assad". La Repubblica (in Italian). Rome. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Givetash, Linda; Lavanga, Claudio (1 July 2020). "Italian police seize 14 tons of amphetamines with possible ISIS link". NBC News. London. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nadeau, Barbie Latza (1 July 2020). "Italian Police on Amalfi Coast Seize 84 Million 'Captagon' Pills Shipped by ISIS From Syria". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ "Captagon: Italy seizes €1bn of amphetamines 'made to fund IS'". BBC News. New York. 1 July 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ "Egyptian police seize container with 1,858 Captagon drug packets". Egypt Independent. 15 November 2020.

- ^ "Attempt to smuggle 11M drug tablets in container thwarted". Egypt Today. 30 November 2020.

- ^ "Captagon: Destroying the frontline drug". BBC. 21 December 2020.

- ^ "Egypt busts massive drugs haul worth Dh143m". Gulf News. 6 January 2021.

- ^ "Lebanon seizes 5m captagon pills at Beirut port". Arab News. 3 February 2021.

- ^ "Lebanon vows to punish drug smugglers as Saudi import ban bites". Arab News. 25 April 2021.

- ^ Lopez, German (20 November 2015). "Captagon, ISIS's favorite amphetamine, explained". Vox.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Henley J (13 January 2014). "Captagon: the amphetamine fuelling Syria's civil war". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ^ "Insight – War turns Syria into major amphetamines producer, consumer". Reuters UK. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ Baker A. "Syria's Breaking Bad: Are Amphetamines Funding the War?". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ "'A dirty business': how one drug is turning Syria into a narco-state". The Guardian. 7 May 2021.

- ^ "14 million Captagon amphetamine pills coming from Lebanon seized". Saudi Gazette. 26 June 2021.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia seizes 4.5m amphetamine pills hidden in oranges". Al Jazeera. 30 June 2021.

- ^ "Saudis bust bid to smuggle 2 million Captagon pills". Gulf News. 24 July 2021.

- Substituted amphetamines

- Xanthines

- Codrugs

- Adenosine receptor antagonists

- Norepinephrine-dopamine releasing agents

- Stimulants

- 1961 introductions

- Illegal drug trade