Pashto

| Pashto | |

|---|---|

| پښتو Pax̌tó | |

The word Pax̌tó written in the Pashto alphabet | |

| Pronunciation | [pəʂˈt̪o], [pʊxˈt̪o], [pəçˈt̪o], [pəʃˈt̪o] |

| Native to | Afghanistan, Pakistan |

| Ethnicity | Pashtuns |

Native speakers | 40–60 million |

Indo-European

| |

Standard forms | |

| Dialects | Pashto dialects |

| Perso-Arabic script (Pashto alphabet) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Pashto Academy Quetta |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ps – Pashto, Pushto |

| ISO 639-2 | pus – Pushto, Pashto |

| ISO 639-3 | pus – inclusive code – Pashto, PushtoIndividual codes: pst – Central Pashtopbu – Northern Pashtopbt – Southern Pashtowne – Wanetsi |

| Glottolog | pash1269 Pashto |

| Linguasphere | 58-ABD-a |

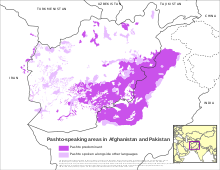

Areas in Afghanistan and Pakistan where Pashto is: the predominant language spoken alongside other languages | |

Pashto (/ˈpʌʃtoʊ/,[3][4][5]/ˈpæʃtoʊ/;[Note 1] پښتو / Pəx̌tó, [pəʂˈt̪o, pʊxˈt̪o, pəʃˈt̪o, pəçˈt̪o]), sometimes spelled Pukhto or Pakhto,[Note 2] is an Eastern Iranian language of the Indo-European family. It is known in Persian literature as Afghani (افغانی, Afghāni).[8]

Spoken as a native language mostly by ethnic Pashtuns, it is one of the two official languages of Afghanistan,[9][1][10] and is the second-largest regional language in Pakistan, mainly spoken in the northwestern province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the northern districts of the Balochistan province.[11] Likewise, it is the primary language of the Pashtun diaspora around the world. The total number of Pashto speakers is at least 40 million,[12] although some estimates place it as high as 60 million.[13] Pashto is "one of the primary markers of ethnic identity" amongst Pashtuns.[14]

Geographic distribution[]

As a national language of Afghanistan,[15] Pashto is primarily spoken in the east, south, and southwest, but also in some northern and western parts of the country. The exact number of speakers is unavailable, but different estimates show that Pashto is the mother tongue of 45–60%[16][17][18][19] of the total population of Afghanistan.

In Pakistan, Pashto is spoken by 15% of its population,[20][21] mainly in the northwestern province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and northern districts of Balochistan province. Pashto-speakers are found in other major cities of Pakistan, most notably in Karachi, Sindh.[22]

Other communities of Pashto speakers are found in India, Tajikistan,[23] and northeastern Iran (primarily in South Khorasan Province to the east of Qaen, near the Afghan border).[24] In India most ethnic Pashtun (Pathan) peoples speak the geographically native Hindi-Urdu language instead of Pashto. However small numbers of Pashto speakers exist in India, namely the Sheen Khalai in Rajasthan,[25] and the Pathan community in the city of Kolkata, often nicknamed the Kabuliwala ("people of Kabul").[26][27]

In addition, sizable Pashtun diaspora also exist in Western Asia, especially in the United Arab Emirates[28] and Saudi Arabia. The Pashtun diaspora speaks Pashto in countries like the United States, United Kingdom,[29] Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, Qatar, Australia, Japan, Russia, New Zealand, etc.

Afghanistan[]

Pashto is one of the two official languages of Afghanistan, along with Dari Persian.[30] Since the early 18th century, the monarchs of Afghanistan have been ethnic Pashtuns (except for Habibullāh Kalakāni in 1929).[31] Persian, the literary language of the royal court,[32] was more widely used in government institutions while the Pashtun tribes spoke Pashto as their native tongue. King Amanullah Khan began promoting Pashto during his reign (1926-1929) as a marker of ethnic identity and as a symbol of "official nationalism"[31] leading Afghanistan to independence after the defeat of the British Empire in the Third Anglo-Afghan War in 1919. In the 1930s a movement began to take hold to promote Pashto as a language of government, administration, and art with the establishment of a Pashto Society Pashto Anjuman in 1931[33] and the inauguration of the Kabul University in 1932 as well as the formation of the Pashto Academy (Pashto Tolana) in 1937.[34]

Although officially supporting the use of Pashto, the Afghan elite regarded Persian as a "sophisticated language and a symbol of cultured upbringing".[31] King Zahir Shah (reigned 1933-1973) thus followed suit after his father Nadir Khan had decreed in 1933 that officials were to study and utilize both Persian and Pashto.[35] In 1936 a royal decree of Zahir Shah formally granted to Pashto the status of an official language[36] with full rights to usage in all aspects of government and education - despite the fact that the ethnically Pashtun royal family and bureaucrats mostly spoke Persian.[34] Thus Pashto became a national language, a symbol for Pashtun nationalism.

The constitutional assembly reaffirmed the status of Pashto as an official language in 1964 when Afghan Persian was officially renamed to Dari.[37][38] The lyrics of the national anthem of Afghanistan are in Pashto.

Pakistan[]

In Pakistan, Pashto is the first language of 15% of its population (as of 1998),[39][21] mainly in the northwestern province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and northern districts of Balochistan province. It is also spoken in parts of Mianwali and Attock districts of the Punjab province, areas of Gilgit-Baltistan and in Islamabad, as well as by Pashtuns who live in different cities throughout the country. Modern Pashto-speaking communities are found in the cities of Karachi and Hyderabad in Sindh.[22][40][41][42]

Urdu and English are the two official languages of Pakistan. Pashto has no official status at the federal level. On a provincial level, Pashto is the regional language of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and north Balochistan.[43] The primary medium of education in government schools in Pakistan is Urdu.[44][45]

The lack of importance given to Pashto and neglect has caused growing resentment amongst Pashtuns, who also complain that Pashto is often neglected officially.[46][47][48][49] It is noted that Pashto is not taught well in schools in Pakistan.[50] Moreover, in government schools material is not provided for in the Pashto dialect of that locality.[51] Students are unable to fully comprehend educational material in Urdu.[52]

Professor Tariq Rahman states:[53]

"The government of Pakistan, faced with irredentist claims from Afghanistan on its territory, also discouraged the Pashto Movement and eventually allowed its use in peripheral domains only after the Pakhtun elite had been co-opted by the ruling elite...Thus, even though there is still an active desire among some Pakhtun activists to use Pashto in the domains of power, it is more of a symbol of Pakhtun identity than one of nationalism."

— Tariq Rahman, The Pashto language and identity‐formation in Pakistan

Robert Nicols states:[54]

"In the end, national language policy, especially in the field of education in the NWFP, had constructed a type of three tiered language hierarchy. Pashto lagged far behind Urdu and English in prestige or development in almost every domain of political or economic power..."

— Language Policy and Language Conflict in Afghanistan and Its Neighbors, Pashto Language Policy and Practice in the North West Frontier Province

History[]

Some linguists have argued that Pashto is descended from Avestan or a variety very similar to it.[55] However, the position that Pashto is a direct descendant of Avestan is not agreed upon. What scholars agree on is the fact that Pashto is an Eastern Iranian language sharing characteristics with Eastern Middle Iranian languages such as Bactrian, Khwarezmian and Sogdian.[56][57]

Strabo, who lived between 64 BC and 24 CE, explains that the tribes inhabiting the lands west of the Indus River were part of Ariana. This was around the time when the area inhabited by the Pashtuns was governed by the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. From the 3rd century CE onward, they are mostly referred to by the name Afghan (Abgan).[58][59][60][8]

Abdul Hai Habibi believed that the earliest modern Pashto work dates back to Amir Kror Suri of the early Ghurid period in the 8th century, and they use the writings found in Pata Khazana. Pə́ṭa Xazāná (پټه خزانه) is a Pashto manuscript[61] claimed to be written by Mohammad Hotak under the patronage of the Pashtun emperor Hussain Hotak in Kandahar; containing an anthology of Pashto poets. However, its authenticity is disputed by scholars such as David Neil MacKenzie and Lucia Serena Loi.[62][63] Nile Green comments in this regard:[64]

"In 1944, Habibi claimed to have discovered an eighteenth-century manuscript anthology containing much older biographies and verses of Pashto poets that stretched back as far as the eighth century. It was an extraordinary claim, implying as it did that the history of Pashto literature reached back further in time than Persian, thus supplanting the hold of Persian over the medieval Afghan past. Although it was later convincingly discredited through formal linguistic analysis, Habibi’s publication of the text under the title Pata Khazana (‘Hidden Treasure’) would (in Afghanistan at least) establish his reputation as a promoter of the wealth and antiquity of Afghanistan’s Pashto culture."

— Afghan History Through Afghan Eyes

From the 16th century, Pashto poetry become very popular among the Pashtuns. Some of those who wrote in Pashto are Bayazid Pir Roshan (a major inventor of the Pashto alphabet), Khushal Khan Khattak, Rahman Baba, Nazo Tokhi, and Ahmad Shah Durrani, founder of the modern state of Afghanistan or the Durrani Empire.

In modern times, noticing the incursion of Persian and Arabic vocabulary, there is a strong desire to "purify" Pashto by restoring its old vocabulary.[65][66][67]

Grammar[]

Pashto is a subject–object–verb (SOV) language with split ergativity. In Pashto, this means that the verb agrees with the subject in transitive and intransitive sentences in non-past, non-completed clauses, but when a completed action is reported in any of the past tenses, the verb agrees with the subject if it is intransitive, but with the object if it is transitive.[15] Verbs are inflected for present, simple past, past progressive, present perfect, and past perfect tenses. There is also an inflection for the subjunctive mood.

Nouns and adjectives are inflected for two genders (masculine and feminine),[68] two numbers (singular and plural), and four cases (direct, oblique, ablative, and vocative). The possessor precedes the possessed in the genitive construction, and adjectives come before the nouns they modify.

Unlike most other Indo-Iranian languages, Pashto uses all three types of adpositions—prepositions, postpositions, and circumpositions.

Phonology[]

Vowels[]

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Mid | e | ə | o |

| Open | a | ɑ |

Consonants[]

| Labial | Denti- alveolar |

Post- alveolar |

Retroflex | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɳ | ŋ | ||||||||||||

| Plosive | p | b | t̪ | d̪ | ʈ | ɖ | k | ɡ | q | |||||||

| Affricate | t͡s | d͡z | t͡ʃ | d͡ʒ | ||||||||||||

| Flap | ɽ | |||||||||||||||

| Fricative | f | s | z | ʃ | ʒ | ʂ | ʐ | ç | ʝ | x | ɣ | h | ||||

| Approximant | l | j | w | |||||||||||||

| Trill | r | |||||||||||||||

- Phonemes that have been borrowed, thus non-native to Pashto, are color coded. The phonemes /q/ and /f/ tend to be replaced by [k] and [p] respectively.[69][Note 3]

- /ɽ/ is voiced back-alveolar retroflex flap.[70] MacKenzie states: "In distinction, from the alveolar trill r and from the dental (or alveolar) lateral l, it is basically a retroflexed lateral flap."[71]

- The retroflex fricatives /ʂ, ʐ/ and palatal fricatives /ç, ʝ/ represent dialectally different pronunciations of the same sound, not separate phonemes. In particular, the retroflex fricatives, which represent the original pronunciation of these sounds, are preserved in the South Western dialects (especially the prestige dialect of Kandahar), while they are pronounced as palatal fricatives in the North Western dialects. Other dialects merge the retroflexes with other existing sounds: The South Eastern dialects merge them with the postalveolar fricatives /ʃ, ʒ/, while the North Eastern dialects merge them with the velar phonemes in an asymmetric pattern, pronouncing them as [x, ɡ]. Furthermore, according to Henderson (1983),[72] the voiced palatal fricative /ʝ/ actually occurs generally in the Wardak Province, and is merged into /ɡ/ elsewhere in the North Western dialects. It is also pronounced as sometimes /ʝ/ in Bati Kot according to the findings of D.W Coyle.[73]

- The velars /k, ɡ, x, ɣ/ followed by the close back rounded vowel /u/ assimilate into the labialized velars [kʷ, ɡʷ, xʷ, ɣʷ].

- Voiceless stops [p, t, t͡ʃ, k] are all unaspirated, like Romance languages, and Austronesian languages; they have slightly aspirated allophones prevocalically in a stressed syllable.

Vocabulary[]

In Pashto, most of the native elements of the lexicon are related to other Eastern Iranian languages.[57] As noted by Josef Elfenbein, "Loanwords have been traced in Pashto as far back as the third century B.C., and include words from Greek and probably Old Persian".[74] For instance, Georg Morgenstierne notes the Pashto word مېچن mečә́n i.e. a hand-mill as being derived from the Ancient Greek word μηχανή (mēkhanḗ, i.e. a device).[75] Post-7th century borrowings came primarily from Persian language and Hindi-Urdu, with Arabic words being borrowed through Persian,[76] but sometimes directly.[77][78] Modern speech borrows words from English, French, and German.[79]

However, a remarkably large number of words are unique to Pashto.[80][81]

Here is an exemplary list of Pure Pashto and borrowings:[82][83][84][85][86]

| Pashto | Persian Loan | Arabic Loan | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| چوپړ čopáṛ |

خدمت khidmat |

خدمة khidmah |

service |

| هڅه hátsa |

کوشش kušeš |

effort/try | |

| ملګری, ملګرې malgə́ray, malgə́re |

دوست dost |

friend | |

| نړۍ

naṛә́i |

جهان

jahān |

دنيا

dunyā |

world |

| تود/توده

tod/táwda |

گرم

garm |

hot | |

| اړتيا

aṛtyā́ |

ضرورة

ḍarurah |

need | |

| هيله

híla |

اميد

umid |

hope | |

| د ... په اړه

də...pə aṛá |

باره

bāra |

about | |

| بوللـه

bolә́la |

قصيدة

qasidah |

an ode |

Classical vocabulary[]

There a lot of old vocabulary that have been replaced by borrowings e.g. پلاز [throne] with تخت [from Persian].[87][88] Or the word يګانګي [yagānagí] meaning "uniqueness" used by Pir Roshan Bayazid.[89] Such classical vocabulary is being reintroduced to modern Pashto.[90] Some words also survive in dialects like ناوې پلاز [the bride-room].[91]

Example from Khayr-al-Bayān:[89]

... بې يګانګئ بې قرارئ وي او په بدخوئ کښې وي په ګناهان

Transliteration: ... be-yagānagə́i, be-kararə́i wi aw pə badxwə́i kx̌e wi pə gunāhā́n

Translation: " ... without singularity/uniqueness, without calmness and by bad-attitude are on sin ."

Writing system[]

Pashto employs the Pashto alphabet, a modified form of the Perso-Arabic alphabet or Arabic script.[92] In the 16th century, Bayazid Pir Roshan introduced 13 new letters to the Pashto alphabet. The alphabet was further modified over the years.

The Pashto alphabet consists of 45 to 46 letters[93] and 4 diacritic marks. In Latin transliteration, stress is represented by the following markers over vowels: ә́, á, ā́, ú, ó, í and é. The following table (read from left to right) gives the letters' isolated forms, along with possible Latin equivalents and typical IPA values:

| ا ā /ɑ, a/ |

ب b /b/ |

پ p /p/ |

ت t /t̪/ |

ټ ṭ /ʈ/ |

ث (s) /s/ |

ج ǧ /d͡ʒ/ |

ځ g, dz /d͡z/ |

چ č /t͡ʃ/ |

څ c, ts /t͡s/ |

ح (h) /h/ |

خ x /x/ |

| د d /d̪/ |

ډ ḍ /ɖ/ |

ﺫ (z) /z/ |

ﺭ r /r/ |

ړ ṛ /ɺ,ɻ, ɽ/ |

ﺯ z /z/ |

ژ ž /ʒ/ |

ږ ǵ (or ẓ̌) /ʐ, ʝ, ɡ, ʒ/ |

س s /s/ |

ش š /ʃ/ |

ښ x̌ (or ṣ̌) /ʂ, ç, x, ʃ/ | |

| ص (s) /s/ |

ض (z) /z/ |

ط (t) /t̪/ |

ظ (z) /z/ |

ع (ā) /ɑ/ |

غ ğ /ɣ/ |

ف f /f/ |

ق q /q/ |

ک k /k/ |

ګ ģ /ɡ/ |

ل l /l/ | |

| م m /m/ |

ن n /n/ |

ڼ ṇ /ɳ/ |

ں ̃ , ń /◌̃/ |

و w, u, o /w, u, o/ |

ه h, a /h, a/ |

ۀ ə /ə/ |

ي y, i /j, i/ |

ې e /e/ |

ی ay, y /ai, j/ |

ۍ əi /əi/ |

ئ əi, y /əi, j/ |

Dialects[]

Pashto dialects are divided into two varieties, the "soft" southern variety Paṣ̌tō, and the "hard" northern variety Pax̌tō (Pakhtu).[94] Each variety is further divided into a number of dialects. The southern dialect of Wanetsi is the most distinctive Pashto dialect.

- Abdaili or Kandahar dialect (or South Western dialect)

- Kakar dialect (or South Eastern dialect)

- Shirani dialect

- Mandokhel dialect

- Marwat-Bettani dialect

- Southern Karlani group

- Khattak dialect

- Wazirwola dialect

- Dawarwola dialect

- Masidwola dialect

- Banisi (Banu) dialect

- Central Ghilji dialect (or North Western dialect)

- Yusapzai and Momand dialect (or North Eastern dialect)

- Northern Karlani group

- Wardak dialect

- Taniwola dialect

- Mangal tribe dialect

- Khosti dialect

- Zadran dialect

- Bangash-Orakzai-Turi-Zazi- dialect

- Afridi dialect

- Khogyani dialect

3. Tareeno Dialect

Literary Pashto[]

Standard Pashto or Literary Pashto is the standardized variety of Pashto which serves as a literary register of Pashto, and is based on the North Western dialect, spoken in the central Ghilji region, including the Afghan capital Kabul and some surrounding region. Literary Pashto's vocabulary, however, also derives from Southern Pashto. This dialect of Pashto has been chosen as standard because it is generally understandable. Standard Pashto is the literary variety of Pashto used in Afghan media.

Literary Pashto has been developed by Radio Television Afghanistan and Academy of Sciences of Afghanistan in Kabul. It has adopted neologisms to coin new terms from already existing words or phrases and introduce them into the Pashto lexicon. Educated Standard Pashto is learned in the curriculum that is taught in the primary schools in the country. It is used for written and formal spoken purposes, and in the domains of media and government.[95]

Criticism[]

There is no actual Pashto that can be identified as "Standard" Pashto, as Colye remarks:[96]

"Standard Pashto is actually fairly complex with multiple varieties or forms. Native speakers or researchers often refer to Standard Pashto without specifying which variety of Standard Pashto they mean...people sometimes refer to Standard Pashto when they mean the most respected or favorite Pashto variety among a majority of Pashtun speakers."

— Placing Wardak among Pashto Varities, page 4

As David MacKenzie notes there is no real need to develop a "Standard" Pashto:[97]

"The morphological differences between the most extreme north-eastern and south-western dialects are comparatively few and unimportant. The criteria of dialect differentiation in Pashto are primarily phonological. With the use of an alphabet which disguises these phonological differences the language has, therefore, been a literary vehicle, widely understood, for at least four centuries. This literary language has long been referred to in the West as 'common' or 'standard' Pashto without, seemingly, any real attempt to define it."

— A Standard Pashto, page 231

There has also been an effort[98] to adopt a written form based on Latin script,[99][100][101][102] but the effort of adapting a Roman alphabet has not gained official support.

Literature[]

Pashto-speakers have long had a tradition of oral literature, including proverbs, stories, and poems. Written Pashto literature saw a rise in development in the 17th century mostly due to poets like Khushal Khan Khattak (1613–1689), who, along with Rahman Baba (1650–1715), is widely regarded as among the greatest Pashto poets. From the time of Ahmad Shah Durrani (1722–1772), Pashto has been the language of the court. The first Pashto teaching text was written during the period of Ahmad Shah Durrani by Pir Mohammad Kakar with the title of Maʿrifat al-Afghānī ("The Knowledge of Afghani [Pashto]"). After that, the first grammar book of Pashto verbs was written in 1805 under the title of Riyāż al-Maḥabbah ("Training in Affection") through the patronage of Nawab Mahabat Khan, son of Hafiz Rahmat Khan, chief of the Barech. Nawabullah Yar Khan, another son of Hafiz Rahmat Khan, in 1808 wrote a book of Pashto words entitled ʿAjāyib al-Lughāt ("Wonders of Languages").

Poetry example[]

An excerpt from the Kalām of Rahman Baba:

زۀ رحمان پۀ خپله ګرم يم چې مين يم

چې دا نور ټوپن مې بولي ګرم په څۀ

Pronunciation: [zə raˈmɑn pə ˈxpəl.a gram jəm t͡ʃe maˈjan jəm

t͡ʃe d̪ɑ nor ʈoˈpən me boˈli gram pə t͡sə]

Transliteration: Zə Rahmā́n pə xpə́la gram yəm če mayán yəm

Če dā nor ṭopə́n me bolí gram pə tsə

Translation: "I Rahman, myself am guilty that I am a lover,

On what does this other universe call me guilty."

Proverbs[]

See: Pashto literature and poetry § Proverbs

Pashto also has a rich heritage of proverbs (Pashto matalúna, sg. matál).[103][104] An example of a proverb:

اوبه په ډانګ نه بېلېږي

Transliteration: Obә́ pə ḍāng nə beléẓ̌i

Translation: "One cannot divide water by [hitting it with] a pole."

Phrases[]

Greeting phrases[]

| Greeting | Pashto | Transliteration | Literal meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hello | ستړی مه شې

ستړې مه شې |

stә́ṛay mә́ še

stә́ṛe mә́ še |

May you not be tired |

| ستړي مه شئ | stә́ṛi mә́ šəi | May you not be tired [said to people] | |

| په خير راغلې | pə xair rā́ğle | With goodness (you) came | |

| Thank you | مننه | manә́na | Acceptance [from the verb منل] |

| Goodbye | په مخه دې ښه | pə mә́kha de x̌á | On your front be good |

| خدای پامان | xwdā́i pāmā́n | From: خدای په امان [With/On God's security] |

Colors[]

List of colors:

WIKI