Van Province

Van Province

Van ili | |

|---|---|

Location of Van Province in Turkey | |

| Country | Turkey |

| Region | Central East Anatolia |

| Subregion | Van |

| Government | |

| • Electoral district | Van |

| • Governor | Mehmet Emin Bilmez |

| Area | |

| • Total | 19,069 km2 (7,363 sq mi) |

| Population (2020)[1] | |

| • Total | 1,149,342 |

| • Density | 60/km2 (160/sq mi) |

| Area code(s) | 0432[2] |

| Vehicle registration | 65 |

Van Province (Turkish: Van ili, Kurdish: Parezgêha Wanê,[3] Armenian: Վանի մարզ) is a province in the Eastern Anatolian region of Turkey, between Lake Van and the Iranian border. It is 19,069 km2 in area and had a population of 1,035,418 at the end of 2010. Its adjacent provinces are Bitlis to the west, Siirt to the southwest, Şırnak and Hakkâri to the south, and Ağrı to the north. The capital of the province is the city of Van. The province is considered part of Western Armenia by Armenians[4] and was part of ancient province of Vaspurakan.[5] The region is considered to be the cradle of Armenian civilization. Before the Armenian genocide, Van Province was part of six Armenian vilayets.[6][7] A majority of the province's modern day population is Kurdish.[8] The current Governor is Mehmet Emin Bilmez.[9]

Demographics[]

The province is mainly populated by Kurds and considered part of Turkish Kurdistan.[10] The province had a significant Armenian population until the genocide in 1915.[11]

In the 1881-1882 Ottoman census, Van Sanjak had a population of 113,964 of which 52.1% was Armenian and 47.9% Muslim.[12] In the 1914 census, the sanjak had a population of 172,171 of which 63.6% was Muslim and 35.7% Armenian. The remaining population was Nestorian Assyrians at 0.5% and Chaldean Assyrians at 0.2%.[13] In the first Turkish census in 1927, Kurdish was the most-spoken first language in Van Province (which included Hakkari Province until 1945) at 76.6% while Turkish remained the second most-spoken first language at 23.1%. Other languages enumerated included Hebrew at 0.2% and Arabic at 0.1%. In the same census, Muslims comprised 99.8% of the population and the remaining 0.2% being Jews.[14] In the subsequent census in 1935, Kurdish stood at 72.4% and Turkish at 27.2%. Other smaller languages included Circassian at 0.2%, Hebrew at 0.1%, Arabic at 0.1%. In regards to religion, Muslims remained the largest denomination at 99.8%, Jews stood at 0.1% and Christians at 0.1%.[15] In 1945, Kurdish stood at 59.9% and Turkish at 39.6%, while 99.9% of the population was Muslim.[16] In 1955, Kurdish and Turkish remained the two most spoken languages at 66.4% and 33.1%, respectively.[17]

History[]

This area was the heartland of Armenians, who lived in these areas from the time of Hayk in the 3rd millennium BCE right up to the late 19th century when the Ottoman Empire seized all the land from the natives.[18] In the 9th century BC the Van area was the center of the Urartian kingdom.[19] The area was a major Armenian population center. The region came under the control of the Armenian Orontids in the 7th century BC and later Persians in the mid-6th century BC. By the early 2nd century BC it was part of the Kingdom of Armenia. It became an important center during the reign of the Armenian king, Tigranes II, who founded the city of Tigranakert in the 1st century BC.[20]

Seljuks and Ottomans[]

With the Seljuq victory at the Battle of Malazgirt in 1071, just north of Lake Van,[21] it became a part of the Seljuq Empire and later the Ottoman Empire during their century long wars with their neighboring Iranian Safavid arch rivals, in which Sultan Selim I managed to conquer the area over the latter. The area continued to be contested and was passed on between the Ottoman Empire and the Safavids (and their subsequent successors, the Afsharids and Qajars) for many centuries until the Battle of Chaldiran which set the borders till this day. During the 19th century it was reorganized as Van Vilayet.

Republic of Turkey[]

In 1927 the office of the Inspector General was created, which governed with martial law.[22] The province was included in the first Inspectorate General (Umumi Müfettişlik, UM) over which the Inspector General ruled. The UM span over the provinces of Hakkâri, Siirt, Van, Mardin, Bitlis, Sanlıurfa, Elaziğ and Diyarbakır.[23] The Inspectorate General were dissolved in 1952 during the Government of the Democrat Party.[24]

Between July 1987 and July 2000 Van Province was within the OHAL region, which was ruled by a Governor within a state of emergency.[25]

Modern history[]

According to the 2012 Metropolitan Municipalities Law (Law No. 6360), all Turkish provinces with a population more than 750 000, will have a metropolitan municipality and the districts within the metropolitan municipalities will be second level municipalities. The law also creates new districts within the provinces in addition to present districts.[26]

Earthquakes[]

In Van province occurred several earthquakes. In 1881 an earthquake occurred and caused the death of 95 people.[27] In 1941, Van suffered a destructive 5.9 Mw earthquake. Two more earthquakes occurred in 2011 in which 644 people died and 2608 people were injured.[27] In a 7.2 Mw earthquake on 23 October 2011, more than 500 people were killed.[28] On 9 November 2011, a 5.6 Mw magnitude earthquake killed also several people and caused buildings to collapse.[27]

Districts[]

Van Province is divided into 14 districts.[29]

Gallery[]

Haykaberd or Çavuştepe

- Medieval Armenian monasteries in the Van Province

The Armenian Cathedral of the Holy Cross (10th century) on Akdamar Island

The Armenian Monastery of Narek (10th century)

Varagavank Armenian monastery (11th century)

The Armenian Monastery of Saint Bartholomew (13th century)

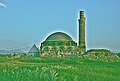

- Islamic monuments in the Van Province

Ruined Ottoman mosque in the old ruined part of Van city (16th century)

Tomb of Halime Hatun in Gevaş (14th century)

Ruined Ottoman minaret in the old part of Van city

See also[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Van Province. |

- Ottoman Armenian Population

- Defense of Van (1915)

- 2011 Van earthquake

- Yazidis

- 2020 Van avalanches

Bibliography[]

Dündar, Fuat (2000), Türkiye nüfus sayımlarında azınlıklar (in Turkish), ISBN 9789758086771

References[]

- ^ "Population of provinces by years - 2000-2018". Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ Area codes page of Turkish Telecom website Archived 2011-08-22 at the Wayback Machine (in Turkish)

- ^ "Li Agirî û Wanê qedexe hat ragihandin" (in Kurdish). Rûdaw. 25 November 2019. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ Myhill, John (2006). Language, Religion and National Identity in Europe and the Middle East: A historical study. Amsterdam: J. Benjamins. p. 32. ISBN 978-90-272-9351-0.

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard G. (1999). Armenian Van/Vaspurakan. Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers. ISBN 1-56859-130-6. Retrieved 2011-01-22.

- ^ İsmail Soysal, Türkiye'nin Siyasal Andlaşmaları, I. Cilt (1920-1945), Türk Tarih Kurumu, 1983, p. 14.

- ^ Verheij, Jelle (2012). Jongerden, Joost; Verheij, Jelle (eds.). Social Relations in Ottoman Diyarbekir, 1870–1915. Brill. p. 88. ISBN 9789004225183.

- ^ Watts, Nicole F. (2010). Activists in Office: Kurdish Politics and Protest in Turkey (Studies in Modernity and National Identity). Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-295-99050-7.

- ^ "T.C. Van Valiliği Resmi Web Sitesi". www.van.gov.tr. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- ^ "Kurds, Kurdistān". Encyclopaedia of Islam (2 ed.). BRILL. 2002. ISBN 9789004161214.

- ^ Anna Grabolle, Celiker (2015). Kurdish Life in Contemporary Turkey: Migration, Gender and Ethnic Identity. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 41. ISBN 9780857725974.

- ^ Karpat, Kemal (October 1978). "Ottoman Population Records and the Census of 1881/82-1893". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 9 (3): 272. doi:10.1017/S0020743800000088. JSTOR 162764 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Karpat, Kemal (1985). Ottoman population 1830-1914. The University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 182–183. ISBN 9780299091606.

- ^ Dündar (2000), pp. 157 & 159.

- ^ Dündar (2000), pp. 163-164 & 168.

- ^ Dündar (2000), pp. 175 & 179-180.

- ^ Dündar (2000), p. 188.

- ^ Hofmann, Tessa, ed. (2004). Verfolgung, Vertreibung und Vernichtung der Christen im Osmanischen Reich 1912-1922 [Persecution, Expulsion and Annihilation of the Christian Population in the Ottoman Empire 1912-1922]. Münster: LIT. ISBN 3-8258-7823-6.

- ^ European History in a World Perspective - p. 68 by Shepard Bancroft Clough

- ^ The Journal of Roman Studies – p. 124 by Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies

- ^ Melissa Snell. "Alp Arslan: Article from the 1911 Encyclopedia". About Education.

- ^ Jongerden, Joost (2007-01-01). The Settlement Issue in Turkey and the Kurds: An Analysis of Spatical Policies, Modernity and War. BRILL. p. 53. ISBN 978-90-04-15557-2.

- ^ Bayir, Derya (2016-04-22). Minorities and Nationalism in Turkish Law. Routledge. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-317-09579-8.

- ^ Fleet, Kate; Kunt, I. Metin; Kasaba, Reşat; Faroqhi, Suraiya (2008-04-17). The Cambridge History of Turkey. Cambridge University Press. p. 343. ISBN 978-0-521-62096-3.

- ^ "Case of Dogan and others v. Turkey" (PDF). p. 21. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

- ^ Official gazette (in Turkish)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Güney, D. "Van earthquakes (23 October 2011 and 9 November 2011) and performance of masonry and adobe structures" (PDF). Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- ^ the CNN Wire Staff. "At least 5 dead in quake in eastern Turkey". CNN. Retrieved 2020-03-01.

- ^ Şafak, Yeni (2019-11-14). "Van Seçim Sonuçları – 31 Mart 2019 Van Yerel Seçim sonuçları". Yeni Şafak (in Turkish). Retrieved 2019-11-14.

External links[]

Coordinates: 38°29′57″N 43°40′13″E / 38.49917°N 43.67028°E

- Van Province

- Armenian Highlands

- Turkish Kurdistan