List of non-standard dates

Several non-standard dates are used in calendars. Some are used sarcastically, some for scientific or mathematical purposes, and some for exceptional or fictional calendars.

January 0[]

January 0 or 0 January is an alternative name for December 31.

In an ephemeris[]

January 0 is the day before January 1 in an annual ephemeris. It keeps the date in the year for which the ephemeris was published, thus avoiding any reference to the previous year, even though it is the same day as December 31 of the previous year.

January 0 also occurs in the epoch for the ephemeris second, "1900 January 0 at 12 hours ephemeris time".[1] 1900 January 0 (at Greenwich Mean Noon) was also the epoch used by Newcomb's Tables of the Sun, which became the epoch for the Dublin Julian day.[2]

In software[]

In Microsoft Excel, the epoch of the 1900 date format is January 0, 1900.[3]

January 1.0 GMT[]

"January 1.0 GMT" in 1925 almanacs was an instant defined to solve the contrast between two different conventions in defining the civil time of referring to midnight as zero hours. "December 31.5 GMT" in 1924 has a similar definition.

February 30[]

February 30 or 30 February is a date that does not occur on the Gregorian calendar, where the month of February contains only 28 days, or 29 days in a leap year. February 30 is usually used as a sarcastic date for referring to something that will never happen or will never be done.[4] However, this date did happen once on the Swedish calendar in 1712.[5] It also appears in some reform calendars.

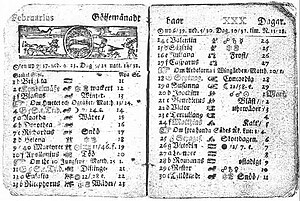

Swedish calendar[]

February 30 was a real date in Sweden in 1712.[5]

Instead of changing from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar by omitting a block of consecutive days, as had been done in other countries, the Swedish Empire planned to change gradually by omitting all leap days from 1700 to 1740, inclusive. Although the leap day was omitted in February 1700, the Great Northern War began later that year, diverting the attention of the Swedes from their calendar so that they did not omit leap days on the next two occasions; 1704 and 1708 remained leap years.[6]

To avoid confusion and further mistakes, the Julian calendar was restored in 1712 by adding an extra leap day, thus giving that year the only known actual use of February 30 in a calendar. That day corresponded to February 29 in the Julian calendar and to March 11 in the Gregorian calendar.[6][7]

The Swedish conversion to the Gregorian calendar was finally accomplished in 1753, when February 17 was followed by March 1.[6]

Artificial calendars[]

Artificial calendars may also have 30 days in February. For example, in a climate model the statistics may be simplified by having 12 months of 30 days. The Hadley Centre General Circulation Model is an example.[8]

Fictional calendars[]

In the works of J. R. R. Tolkien, the Hobbits have developed the Shire Reckoning. According to Appendix D of The Lord of the Rings, this calendar has arranged the year in 12 months of 30 days each. The month the Hobbits call Solmath is rendered in the text as February, and therefore the date February 30 exists in the narrative.[9]

February 30, 1951, is the last night of the world in Ray Bradbury's short story "Last Night of the World".[10]

Myths[]

Soviet calendar[]

Although many sources erroneously state that 30-day months were used in the Soviet Union for part or all of the period from 1929 to 1940, the Soviet calendar with 5- and 6-day weeks was used only for assigning workdays and days of rest in factories. The Gregorian calendar (since 1918) remained for everyday use: surviving physical calendars from that period show only the irregular months of the Gregorian calendar, including a 28- or 29-day February, so there was never a February 30 in the Soviet Union.

Early Julian calendar[]

The thirteenth-century scholar Johannes de Sacrobosco claimed that in the Julian calendar February had 30 days in leap years from 45 BC until 8 BC, when Augustus allegedly shortened February by one day to give that day to the month of August named after him so that it had the same length as the month of July named after his adoptive father, Julius Caesar. However, all historical evidence refutes Sacrobosco, including dual dates with the Alexandrian calendar.[11]

February 31[]

February 31 or 31 February is exceptionally used on gravestones when the date is unknown,[12][better source needed] or in at least one case out of superstition.[13]

It is also used (along with February 32 and February 33) for calculating weather data.[14]

March 0[]

March 0 or 0 March is an alternative name for the last day of February (February 28, or February 29 in leap years). It is used most often in astronomy, software engineering,[15] and Doomsday Algorithm calculations.

May 35[]

May 35 or 35 May is used in mainland China to avoid censorship when referring to the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, where the official names are strictly censored by the Communist government, and the event is normally referred to as June 4.[16] It is also used in the title of The 35th of May, or Conrad's Ride to the South Seas, a German children's novel published in 1931.

June 31[]

June 31 is a fictional date in the Soviet film 31 June.

It is also the date of a fictional RAF raid on Germany in Len Deighton's 1970 novel Bomber.

December 31.5 GMT[]

"December 31.5 GMT" in 1924 almanacs was an instant defined to solve the contrast between two different conventions in defining the civil time of referring to midnight as zero hours.

December 32[]

December 32 or 32 December is the date of Hogswatchnight in Hogfather by Terry Pratchett. It has also been used as a title for various works.

December 32, 1980[]

The LearAvia Lear Fan aircraft test flight had British government "funding that expired at the end of that year." After the cancellation of a planned test flight on December 31, 1980, due to technical issues, the first prototype made its maiden flight on January 1, 1981, but the date was officially recorded by sympathetic British government officials as "December 32, 1980".[17]

Reform calendars[]

Because evening out the months is a part of the rationale for reforming the calendar, some reform calendars, such as the World Calendar and the Hanke–Henry Permanent Calendar, contain a 30-day February. The Symmetry454 calendar assigns 35 days to February, May, August, and November, as well as December in a leap year.

See also[]

- Ides of March

- List of calendars

- System time

- Tibb's Eve, a day said to occur neither before nor after Christmas

- When pigs fly

References[]

- ^ "Leap Seconds". Time Service Department, United States Naval Observatory. Archived from the original on February 28, 2012. Retrieved December 31, 2006.

- ^ Ransom, Jr., David H. (November 19, 1989). "Program ASTROCLK: Astronomical Clock and Celestial Tracking Program with Celestial Navigation". p. 110.

- ^ Lowe, Scott (May 11, 2007). "How do I... Perform basic formatting in Excel 2003?". TechRepublic.

- ^ "Thirty Days Hath February 2000?". About.com. Archived from the original on August 21, 2016. Retrieved November 7, 2013.

- ^ a b "February 30 Was a Real Date". timeanddate.com. Retrieved April 25, 2016.

- ^ a b c Bauer, R. W. (1868). Calender for Aarene fra 601 til 2200. Copenhagen, Denmark: Dansk Historisk Fællesråd (1993 reprint). p. 100. ISBN 87-7423-083-2.

- ^ Vallerius, Johannes (1711). Allmanach på åhret effter Christi födelse 1712. Lund, Sweden.

- ^ "Hadley Centre: GDT netCDF conventions". MetOffice.com. November 22, 2005. Archived from the original on November 22, 2005. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1965). "Appendix D". The Return of the King (2nd ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. ISBN 978-0-395-08256-0.

- ^ "A Classic Ray Bradbury Esquire Story". esquire.com. June 6, 2012. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- ^ Roscoe Lamont, "The Roman calendar and its reformation by Julius Caesar", Popular Astronomy 27 (1919) 583–595. Sacrobosco's theory is discussed on pages 585–587.

- ^ "February 31 On Gravestone". Swampy Acres Farm Blog. December 19, 2018. Archived from the original on December 19, 2018. Retrieved June 13, 2019.

- ^ Troy Taylor (2005). Weird Illinois. Sterling Publishing Co., Inc. p. 212. ISBN 9780760759431.

- ^ J. D. Everett (1863). "Description of a method of Reducing Observations of Temperature". The American Journal of Science and Arts. S. Converse: 23.

- ^

- Astronomical Almanac for the year 2003, Washington and London: U.S Government Printing Office and The Stationery Office, 2001, p. K2, Bibcode:2001asal.book.....U

- Simon Ramo, Ronald Sugar (April 12, 2009), Strategic Business Forecasting: A Structured Approach to Shaping the Future, ISBN 9780071608909

- ^ "China tightens information controls for Tiananmen anniversary". The Age. Australia. Agence France-Presse. June 4, 2009. Retrieved November 3, 2010.

- ^ "Lear Fan 2100 (Futura)". The Museum of Flight. 2009. Archived from the original on July 12, 2009. Retrieved November 27, 2009.

- The Oxford Companion to the Year. Bonnie Blackburn & Leofranc Holford-Strevens. Oxford University Press 1999. ISBN 0-19-214231-3. Pages 98–99.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to List of non-standard dates. |

- 30 days in February 1712

- Change of calendars - Sweden (in Swedish)

- 30 February on Tolkien Gateway

- February

- 1712 in Sweden

- English-language idioms

- January

- December

- 0 (number)

- Lists of things considered unusual