Ergine

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2007) |

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | LSA; d-Lysergic acid amide; d-Lysergamide; Ergine; LA-111 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral, intramuscular injection |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

show

IUPAC name | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.841 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

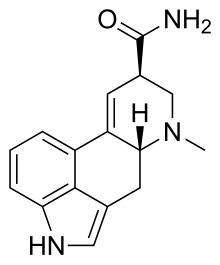

| Formula | C16H17N3O |

| Molar mass | 267.332 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 135 °C (275 °F) Decomposes[3] |

show

SMILES | |

show

InChI | |

Ergine, also known as d-lysergic acid amide (LSA) and d-lysergamide, is an ergoline alkaloid which causes psychedelic hallucinations similar to LSD and occurs in various species of vines of the Convolvulaceae and some species of fungi. The psychedelic properties in the seeds of ololiuhqui, Hawaiian baby woodrose and morning glories have been linked to ergine and/or isoergine, its epimer, as it is the dominant alkaloid present in the seeds.[4][5][6]

Occurrence in nature[]

Ergine has been found in high concentrations of 20 μg/g dry weight in the sleepygrass infected with an Acremonium endophytic fungus together with other ergot alkaloids.[7]

Ergine is a component of the alkaloids contained in the ergot fungus, which grows on the heads of infected rye grasses.

It is also found in the seeds of several varieties of morning glories in concentrations of approximately 10 μg per seed, as well as Hawaiian baby woodrose seeds, at a concentration of around 0.13% of dry weight.[8]

History[]

Ololiuhqui was used by South American healers in shamanic healing ceremonies.[9] Similarly, ingestion of morning glory seeds by Mazatec tribes to "commune with their gods" was reported by Richard Schultes in 1941 and is still practiced today.[10][9]

Additional reports of the use of ergine were made by Don Thomes MacDougall. He reported that the seeds of Ipomoea violacea were used as sacraments by certain Zapotecs, sometimes in conjunction with the seeds of Rivea corymbosa, another species which has a similar chemical composition, with lysergol instead of ergometrine.[11]

Ergine was assayed for human activity by Albert Hofmann in self-trials in 1947, well before it was known to be a natural compound. Intramuscular administration of a 500 microgram dose led to a tired, dreamy state, with an inability to maintain clear thoughts. After a short period of sleep the effects were gone, and normal baseline was recovered within five hours.[12]

In 1956, the Central Intelligence Agency conducted research on the psychedelic properties of the ergine in the seeds of Rivea corymbosa, as Subproject 22 of MKULTRA.[13]

In 1959, Hofmann was the first to isolate chemically pure ergine from the seeds of Turbina corymbosa, determining that it, and other alkaloids, were acting as the main active components in the seeds.[11] 20 years prior to its isolation, ergine was first chemically defined by English chemists S. Smith and G. M. Timmis as the cleavage product of ergot alkaloids. Additionally, Guarin and Youngkin reportedly isolated the crude alkaloid in 1964 from morning glory seeds.[14]

Ingestion[]

Like other psychedelics, ergine is not considered to be addictive. Additionally, there are no known deaths directly associated with pharmacological effects of ergine consumption. All associated deaths are due to indirect causes, such as self-harm, impaired judgement, and adverse drug interactions. One known case involved a suicide that was reported in 1964 after ingestion of morning glory seeds.[15] Another instance is a death due to falling off of a building after ingestion of Hawaiian baby woodrose seeds and alcohol.[16]

Physiological effects[]

While its physiological effects vary from person to person, the following symptoms have been attributed to the consumption of ergine or ergine containing seeds:[17][18][19]

- Sedation

- Mild visual and auditory hallucinations

- Euphoria

- Loss of motor control

- Nausea

- Vasoconstriction

- Pupil dilation

- Delusion

- Anxiety

- Paranoia

- Irregular heartbeat[20]

- Sexual arousal[21]

- tachycardia[22]

- mydriasis[23]

- hypertonia[24]

- respiratory disturbances[25]

- cramps[26]

One study found that 2 of 4 human subjects experienced cardiovascular dysregulation and the study had to be halted, concluding that the drug is more dangerous than commonly believed. The same study also observed that reactions were highly differing in type and intensity between different subjects.[27] Another study in mice found that the drug had aphrodisiac properties, inducing increased sexual behavior.[28]

A study gave mice 3000 mg/kg (the equivalent of giving a 100 kg [220 pounds] person a 300 gram [10.5 ounces] dose) with no lethal effects.

Psychedelic component[]

Ergine is thought to be a serotonergic psychedelic and its psychedelic effects are thought to be due to it being a partial agonist of the 5-HT2A receptor. Though, the reason as to why this may be hallucinogenic remains elusive.

The idea that ergine is the main psychedelic component in ergine containing seeds (morning glory, Hawaiian baby woodrose) is well debated, as the effects of isolated synthetic ergine are reported to be only mildly psychedelic.[29][19] Thus, the overall psychedelic experience after consumption of such seeds has been proposed to be due to a mixture of ergoline alkaloids.

Pharmacology[]

Pharmacodynamics[]

| Receptor | Affinity (Ki [nM]) | |

|---|---|---|

| LSA | LSD | |

| 5-HT1A | 10 | 2.5 |

| 5-HT2 | 28 | 0.87 |

| D1 | 832 | 87 |

| D2L | 891 | 155 |

| D2S | 145 | 25 |

| D3 | 437 | 65 |

| D4.4 | 141 | 30 |

| α1 | 912 | 60 |

| α2 | 62 | 1.0 |

| Notes: 5-HT1A and D1 are for pig receptors.[30] | ||

Ergine interacts with serotonin, dopamine, and adrenergic receptors similarly to but with lower affinity than lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD).[30] The psychedelic effects of ergine can be attributed to activation of serotonin 5-HT2A receptors.[31]

Chemistry[]

Biosynthesis[]

The biosynthetic pathway to ergine starts like most other ergoline alkaloid- with the formation of the ergoline scaffold. This synthesis starts with the prenylation of L-tryptophan in an SN1 fashion with dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) as the prenyl donor and catalyzed by prenyltransferase 4-dimethylallyltryptophan synthase (DMATS), to form 4-L-dimethylallyltryptophan (4-L-DMAT). The DMAPP is derived from mevalonic acid. A three strep mechanism is proposed to form 4-L-DMAT: the formation of an allylic carbocation, a nucleophilic attack of the indole nucleus to the cation, followed by deprotonation to restore aromaticity and to generate 4-L-DMAT.[32] 4-Dimethylallyltyptophan N-methyltransferase (EasF) catalyzes the N-methylation of 4-L-DMAT at the amino of the tryptophan backbone, using S-Adenosyl methionine (SAM) as the methyl source, to form 4-dimethylallyl-L-abrine (4-DMA-L-abrine).[32] The conversion of 4-DMA-L-abrine to chanoclavine-I is thought to occur through a decarboxylation and two oxidation steps, catalyzed by the FAD dependent oxidoreductase, EasE, and the catalase, EasC. The chanoclavine intermediate is then oxidized to chanoclavine-l-aldehyde, catalyzed by the short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR), EasD.[32][33]

From here, the biosynthesis diverges and the products formed are plant and fungus-specific. The biosynthesis of ergine in Claviceps purpurea will be exemplified, in which agroclavine is produced following the formation of chanoclavine-l-aldehyde, catalyzed by EasA through a keto-enol tautomerization to facilitate rotation about the C-C bond, followed by tautomerization back to the aldehyde and condensation with the proximal secondary amine to form an iminium species, which is subsequently reduced to the tertiary amine and yielding argoclavine.[32][33] Cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYP450) are then thought to catalyze the formation of elymoclavine from argoclavine via a 2 electron oxidation. This is further converted to paspalic acid via a 4 electron oxidation, catalyzed by cloA, a CYP450 monooxygenase. Paspalic acid then undergoes isomerization of the C-C double bond in conjugation with the acid to form D-lysergic acid.[32] While the specifics of the formation of ergine from D-lysergic acid are not known, it is proposed to occur through a nonribosomal peptide synthase (NRPS) with two enzymes primarily involve: D-lysergyl peptide synthase (LPS) 1 and 2.[32][33]

Legal status[]

The legality of consuming, cultivating, and possessing ergine varies depending on the country.

There are no laws against possession of ergine-containing seeds in the USA. However, possession of the pure compound without a prescription or DEA license would be prosecuted, as ergine, under the name "lysergic acid amide", is listed under Schedule III of the Controlled Substances Act.[34] Similarly, ergine is considered a Class A substance in the United Kingdom, categorized as a precursor to LSD.

In most Australian states, the consumption of ergine containing materials is prohibited under state legislation.

In Canada, ergine is not illegal to possess as it is not listed under Canada's Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, though it is likely illegal to sell for human consumption.[35]

In New Zealand, ergine is a controlled drug, however the plants and seeds of the morning glory species are legal to possess, cultivate, buy, and distribute.

See also[]

- List of entheogenic/hallucinogenic species

- List of psychoactive plants

- Tlitliltzin (Ipomoea violacea)

Notes[]

- Powell, William (2002). The Anarchist Cookbook. Ozark Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-8488-1130-3.

- Smith, Sydney; Timmis, Geoffrey M. (1932). "98. The Alkaloids of Ergot. Part III. Ergine, a New Base obtained by the Degradation of Ergotoxine and Ergotinine". J. Chem. Soc. 1932: 763–766. doi:10.1039/JR9320000763.

- Juszczak, Grzegorz R.; Swiergiel, Artur H. (2013-01-01). "Recreational use of D-lysergamide from the seeds of Argyreia nervosa, Ipomoea tricolor, Ipomoea violacea, and Ipomoea purpurea in Poland". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 45 (1): 79–93. doi:10.1080/02791072.2013.763570. ISSN 0279-1072. PMID 23662334. S2CID 22086799.

- Burillo-Putze, G.; López Briz, E.; Climent Díaz, B.; Munné Mas, P.; Nogue Xarau, S.; Pinillos, M. A.; Hoffman, R. S. (2013-09-01). "[Emergent drugs (III): hallucinogenic plants and mushrooms]". Anales del Sistema Sanitario de Navarra. 36 (3): 505–518. doi:10.4321/s1137-66272013000300015. ISSN 1137-6627. PMID 24406363.

References[]

- ^ Erowid Morning Glory Basics, Erowid.org, retrieved 2012-02-03

- ^ "Arrêté du 20 mai 2021 modifiant l'arrêté du 22 février 1990 fixant la liste des substances classées comme stupéfiants". www.legifrance.gouv.fr (in French). 20 May 2021.

- ^ Smith, Sydney; Timmis, Geoffrey Millward (1932). "98. The alkaloids of ergot. Part III. Ergine, a new base obtained by the degradation of ergotoxine and ergotinine". Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed): 763. doi:10.1039/jr9320000763.

- ^ Perrine, Daniel M. (2000). "Mixing the Kykeon" (PDF). ELEUSIS: Journal of Psychoactive Plants and Compounds. New Series 4: 9.

- ^ Alexander Shulgin, "#26. LSD-25", TiHKAL, Erowid.org, retrieved 2012-02-03

- ^ Hofmann, Albert (2009). LSD My Problem Child: Reflections on Sacred Drugs, Mysticism, and Science (4th ed.). MAPS.org. ISBN 978-0979862229.

- ^ Petroski RJ, Powell RG, Clay K (1992). "Alkaloids of Stipa robusta (sleepygrass) infected with an Acremonium endophyte". Nat. Toxins. 1 (2): 84–88. doi:10.1002/nt.2620010205. PMID 1344912. Archived from the original on 2012-12-16.

- ^ Chao JM, Der Marderosian AH (1973). "Ergoline alkaloidal constituents of Hawaiian baby wood rose, Argyreia nervosa (Burmf) Bojer". J. Pharm. Sci. 62 (4): 588–91. doi:10.1002/jps.2600620409. PMID 4698977.

- ^ Schultes, Richard E. (1941). A Contribution to Our Knowledge of Rivea Corymbosa: The Narcotic Ololinqui of the Aztecs (1st ed.). Botanical Museum of Harvard University.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hofmann, Albert (2009). LSD My Problem Child: Reflections on Sacred Drugs, Mysticism, and Science (4th ed.). MAPS.org. ISBN 978-0979862229.

- ^ Alexander Shulgin, "#26. LSD-25", TiHKAL, Erowid.org, retrieved 2012-02-03

- ^ "PROJECT MKULTRA, SUBPROJECT 22 (W/ATTACHMENTS)". Central Intelligence Agency.

- ^ Der Mardersian, Ara H.; Guarino, Anthony M.; De Feo, John J.; Youngken, Jr (1964). "A Uterine Stimulant Effect of Extracts of Morning Glory Seeds". Pschedelic Review: 317–323.

- ^ Cohen, Sidney (1964). "Suicide Following Morning Glory Seed Ingestion". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 120 (1): 1024–1025. doi:10.1176/ajp.120.10.1024. PMID 14138842.

- ^ Klinke, Helene; Irene Breum Müller; Steffen Steffenrud; Rasmus Dahl-Sørensen (15 April 2010). "Two cases of lysergamide intoxication by ingestion of seeds from Hawaiian Baby Woodrose". Forensic Science International. 197 (1): e1–e5. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2009.11.017. PMID 20018470.

- ^ Hofmann, Albert (2009). LSD My Problem Child: Reflections on Sacred Drugs, Mysticism, and Science (4th ed.). MAPS.org. ISBN 978-0979862229.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ingram Jr., Albert L. (1964). "Morning Glory Seed Reaction". JAMA (13 ed.). 190 (13): 1133–1134. doi:10.1001/jama.1964.03070260045019. PMID 14212309.

- ^ Kremer, C., Paulke, A., Wunder, C., & Toennes, S. W. (2012). Variable adverse effects in subjects after ingestion of equal doses of Argyreia nervosa seeds. Forensic science international, 214(1-3), e6-e8.

- ^ Subramoniam, A., Madhavachandran, V., Ravi, K., & Anuja, V. S. (2007). Aphrodisiac property of the elephant creeper Argyreia nervosa. J Endocrinol Reprod, 11(2), 82-85.

- ^ Marneros A, Gutmann P, Uhlmann F. Self-amputation of penis and tongue after use of Angel's Trumpet. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006 Oct;256(7):458-9. doi: 10.1007/s00406-006-0666-2. Epub 2006 Jun 16. PMID: 16783491.

- ^ Marneros A, Gutmann P, Uhlmann F. Self-amputation of penis and tongue after use of Angel's Trumpet. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006 Oct;256(7):458-9. doi: 10.1007/s00406-006-0666-2. Epub 2006 Jun 16. PMID: 16783491.

- ^ Marneros A, Gutmann P, Uhlmann F. Self-amputation of penis and tongue after use of Angel's Trumpet. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006 Oct;256(7):458-9. doi: 10.1007/s00406-006-0666-2. Epub 2006 Jun 16. PMID: 16783491.

- ^ Marneros A, Gutmann P, Uhlmann F. Self-amputation of penis and tongue after use of Angel's Trumpet. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006 Oct;256(7):458-9. doi: 10.1007/s00406-006-0666-2. Epub 2006 Jun 16. PMID: 16783491.

- ^ Marneros A, Gutmann P, Uhlmann F. Self-amputation of penis and tongue after use of Angel's Trumpet. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006 Oct;256(7):458-9. doi: 10.1007/s00406-006-0666-2. Epub 2006 Jun 16. PMID: 16783491.

- ^ Kremer, C., Paulke, A., Wunder, C., & Toennes, S. W. (2012). Variable adverse effects in subjects after ingestion of equal doses of Argyreia nervosa seeds. Forensic science international, 214(1-3), e6-e8.

- ^ Subramoniam, A., Madhavachandran, V., Ravi, K., & Anuja, V. S. (2007). Aphrodisiac property of the elephant creeper Argyreia nervosa. J Endocrinol Reprod, 11(2), 82-85.

- ^ Chao JM, Der Marderosian AH (1973). "Ergoline alkaloidal constituents of Hawaiian baby wood rose, Argyreia nervosa (Burmf) Bojer". J. Pharm. Sci. 62 (4): 588–91. doi:10.1002/jps.2600620409. PMID 4698977.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Paulke A, Kremer C, Wunder C, Achenbach J, Djahanschiri B, Elias A, Schwed JS, Hübner H, Gmeiner P, Proschak E, Toennes SW, Stark H (July 2013). "Argyreia nervosa (Burm. f.): receptor profiling of lysergic acid amide and other potential psychedelic LSD-like compounds by computational and binding assay approaches". J Ethnopharmacol. 148 (2): 492–7. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2013.04.044. PMID 23665164.

- ^ Halberstadt, Adam L.; Nichols, David E. (2020). "Serotonin and serotonin receptors in hallucinogen action". Handbook of the Behavioral Neurobiology of Serotonin. Handbook of Behavioral Neuroscience. 31. pp. 843–863. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-64125-0.00043-8. ISBN 9780444641250. ISSN 1569-7339.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Gerhards, Nina; Neubauer, Lisa; Tudzynski, Paul; Li, Shu-Ming (2014-12-10). "Biosynthetic Pathways of Ergot Alkaloids". Toxins. 6 (12): 3281–3295. doi:10.3390/toxins6123281. ISSN 2072-6651. PMC 4280535. PMID 25513893.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Willingale, J.; Atwell, S. M.; Mantle, P. G. (1983-07-01). "Unusual Ergot Alkaloid Biosynthesis in Sclerotia of a Claviceps purpurea Mutant". Microbiology. 129 (7): 2109–2115. doi:10.1099/00221287-129-7-2109. ISSN 1350-0872.

- ^ "Initial schedules of controlled substances (Schedule III), Section 812". www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov. Retrieved 2020-01-17.

- ^ "Erowid LSA Vault : Legal Status". erowid.org. Retrieved 2020-05-05.

External links[]

- Drugs not assigned an ATC code

- Alkaloids found in fungi

- Lysergamides

- Plant toxins

- Quinoline alkaloids

- Serotonin receptor agonists

- Tryptamine alkaloids

- Vasoconstrictors