L-DOPA

Skeletal formula of L-DOPA | |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌɛlˈdoʊpə/, /ˌlɛvoʊˈdoʊpə/ |

| Trade names | Larodopa, Dopar, Inbrija, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Professional Drug Facts |

| MedlinePlus | a619018 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 30% |

| Metabolism | Aromatic-l-amino-acid decarboxylase |

| Elimination half-life | 0.75–1.5 hours |

| Excretion | renal 70–80% |

| Identifiers | |

show

IUPAC name | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.405 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

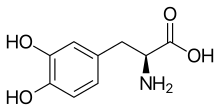

| Formula | C9H11NO4 |

| Molar mass | 197.190 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

show

SMILES | |

show

InChI | |

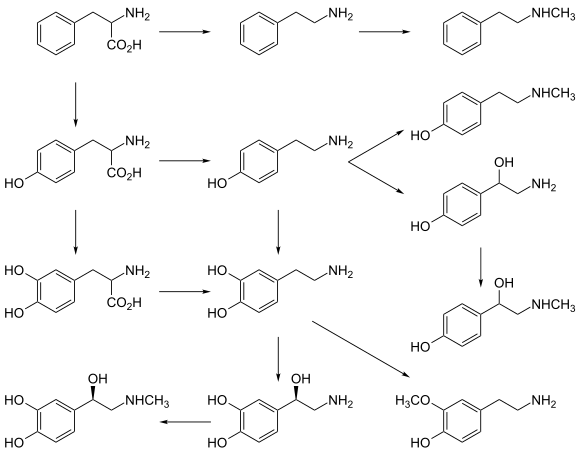

l-DOPA, also known as levodopa and l-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine, is an amino acid that is made and used as part of the normal biology of humans, as well as some animals and plants. Humans, as well as a portion of the other animals that utilize l-DOPA in their biology, make it via biosynthesis from the amino acid l-tyrosine. l-DOPA is the precursor to the neurotransmitters dopamine, norepinephrine (noradrenaline), and epinephrine (adrenaline), which are collectively known as catecholamines. Furthermore, l-DOPA itself mediates neurotrophic factor release by the brain and CNS.[3][4] l-DOPA can be manufactured and in its pure form is sold as a psychoactive drug with the INN levodopa; trade names include Sinemet, Pharmacopa, Atamet, and Stalevo. As a drug, it is used in the clinical treatment of Parkinson's disease and dopamine-responsive dystonia.

l-DOPA has a counterpart with opposite chirality, d-DOPA. As is true for many molecules, the human body produces only one of these isomers (the l-DOPA form). The enantiomeric purity of l-DOPA may be analyzed by determination of the optical rotation or by chiral thin-layer chromatography (chiral TLC).[5]

Medical use[]

l-DOPA crosses the protective blood-brain barrier, whereas dopamine itself cannot.[6] Thus, l-DOPA is used to increase dopamine concentrations in the treatment of Parkinson's disease and dopamine-responsive dystonia. Once l-DOPA has entered the central nervous system, it is converted into dopamine by the enzyme aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase, also known as DOPA decarboxylase. Pyridoxal phosphate (vitamin B6) is a required cofactor in this reaction, and may occasionally be administered along with l-DOPA, usually in the form of pyridoxine.

In humans, conversion of l-DOPA to dopamine does not only occur within the central nervous system. Cells in the peripheral nervous system perform the same task. Thus administering l-DOPA alone will lead to increased dopamine signaling in the periphery as well. Excessive peripheral dopamine signaling is undesirable as it causes many of the adverse side effects seen with sole L-DOPA administration. To bypass these effects, it is standard clinical practice to coadminister (with l-DOPA) a peripheral DOPA decarboxylase inhibitor (DDCI) such as carbidopa (medicines containing carbidopa, either alone or in combination with l-DOPA, are branded as Lodosyn[7] (Aton Pharma)[8] Sinemet (Merck Sharp & Dohme Limited), Pharmacopa (Jazz Pharmaceuticals), Atamet (UCB), Syndopa and Stalevo (Orion Corporation) or with a benserazide (combination medicines are branded Madopar or Prolopa), to prevent the peripheral synthesis of dopamine from l-DOPA).

Inbrija (previously known as CVT-301) is an inhaled powder formulation of levodopa indicated for the intermittent treatment of off episodes in patients with Parkinson's disease currently taking carbidopa/levodopa.[9] It was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration on December 21, 2018 and is marketed by Acorda Therapeutics.[10]

Coadministration of pyridoxine without a DDCI accelerates the peripheral decarboxylation of l-DOPA to such an extent that it negates the effects of l-DOPA administration, a phenomenon that historically caused great confusion.

In addition, l-DOPA, co-administered with a peripheral DDCI, is efficacious for the short term treatment of restless leg syndrome.[11]

The two types of response seen with administration of l-DOPA are:

- The short-duration response is related to the half-life of the drug.

- The longer-duration response depends on the accumulation of effects over at least two weeks, during which ΔFosB accumulates in nigrostriatal neurons. In the treatment of Parkinson's disease, this response is evident only in early therapy, as the inability of the brain to store dopamine is not yet a concern.

Biological role[]

l-DOPA is produced from the amino acid l-tyrosine by the enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase. l-DOPA can act as an l-tyrosine mimetic and be incorporated into proteins by mammalian cells in place of L-tyrosine, generating protease-resistant and aggregate-prone proteins in vitro and may contribute to neurotoxicity with chronic l-DOPA administration.[15] It is also the precursor for the monoamine or catecholamine neurotransmitters dopamine, norepinephrine (noradrenaline), and epinephrine (adrenaline). Dopamine is formed by the decarboxylation of l-DOPA by aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC).

l-DOPA can be directly metabolized by catechol-O-methyl transferase to 3-O-methyldopa, and then further to . This metabolic pathway is nonexistent in the healthy body, but becomes important after peripheral l-DOPA administration in patients with Parkinson's disease or in the rare cases of patients with AADC enzyme deficiency.[16]

l-Phenylalanine, l-tyrosine, and l-DOPA are all precursors to the biological pigment melanin. The enzyme tyrosinase catalyzes the oxidation of l-DOPA to the reactive intermediate dopaquinone, which reacts further, eventually leading to melanin oligomers. In addition, tyrosinase can convert tyrosine directly to l-DOPA in the presence of a reducing agent such as ascorbic acid.[17]

Side effects and adverse reactions[]

The side effects of l-DOPA may include:

- Hypertension, especially if the dosage is too high

- Arrhythmias, although these are uncommon

- Nausea, which is often reduced by taking the drug with food, although protein reduces drug absorption. l-DOPA is an amino acid, so protein competitively inhibits l-DOPA absorption.

- Gastrointestinal bleeding

- Disturbed respiration, which is not always harmful, and can actually benefit patients with upper airway obstruction

- Hair loss

- Disorientation and confusion

- Extreme emotional states, particularly anxiety, but also excessive libido

- Vivid dreams or insomnia

- Auditory or visual hallucinations

- Effects on learning; some evidence indicates it improves working memory, while impairing other complex functions

- Somnolence and narcolepsy

- A condition similar to stimulant psychosis

Although many adverse effects are associated with l-DOPA, in particular psychiatric ones, it has fewer than other antiparkinsonian agents, such as anticholinergics and dopamine receptor agonists.

More serious are the effects of chronic l-DOPA administration in the treatment of Parkinson's disease, which include:

- End-of-dose deterioration of function

- On/off oscillations

- Freezing during movement

- Dose failure (drug resistance)

- Dyskinesia at peak dose (levodopa-induced dyskinesia)

- Possible dopamine dysregulation: The long-term use of l-DOPA in Parkinson's disease has been linked to the so-called dopamine dysregulation syndrome.[18]

Clinicians try to avoid these side effects and adverse reactions by limiting l-DOPA doses as much as possible until absolutely necessary.

The long term use of L-Dopa increases oxidative stress through monoamine oxidase led enzymatic degradation of synthesized dopamine causing neuronal damage and cytotoxicity. The oxidative stress is caused by the formation of reactive oxygen species (H2O2) during the monoamine oxidase led metabolism of dopamine. It is further perpetuated by the richness of Fe2+ ions in striatum via the Fenton reaction and the intracellular auto-oxidation. The increased oxidation can potentially cause mutations in the DNA due to the formation of 8-oxoguanine which is capable of pairing with adenosine.[19]

History[]

In work that earned him a Nobel Prize in 2000, Swedish scientist Arvid Carlsson first showed in the 1950s that administering l-DOPA to animals with drug-induced (reserpine) Parkinsonian symptoms caused a reduction in the intensity of the animals' symptoms. In 1960/61 Oleh Hornykiewicz, after discovering greatly reduced levels of dopamine in autopsied brains of patients with Parkinson's disease,[20] published together with the neurologist dramatic therapeutic antiparkinson effects of intravenously administered l-DOPA in patients.[21] This treatment was later extended to manganese poisoning and later Parkinsonism by George Cotzias and his coworkers,[22] for which they won the 1969 Lasker Prize.,[23][24] who used greatly increased oral doses. The neurologist Oliver Sacks describes this treatment in human patients with encephalitis lethargica in his book Awakenings, upon which the movie of the same name is based. The first study reporting improvements in patients with Parkinson's disease resulting from treatment with L-dopa was published in 1968.[25]

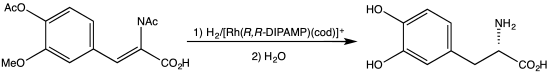

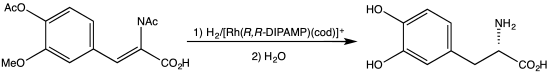

The 2001 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was also related to l-DOPA: the Nobel Committee awarded one-quarter of the prize to William S. Knowles for his work on chirally catalysed hydrogenation reactions, the most noted example of which was used for the synthesis of l-DOPA.[26][27][28]

Synthesis of l-DOPA via hydrogenation with C2-symmetric diphosphine.

Synthesis of l-DOPA via hydrogenation with C2-symmetric diphosphine.

Dietary supplements[]

Herbal extracts containing l-DOPA are available; high-yielding sources include Mucuna pruriens (velvet bean),[29] and Vicia faba (broad bean), while other sources include the genera Phanera, Piliostigma, Cassia, Canavalia, and Dalbergia.[30]

Marine adhesion[]

l-DOPA is a key compound in the formation of , such as those found in mussels.[31][32] It is believed to be responsible for the water-resistance and rapid curing abilities of these proteins. l-DOPA may also be used to prevent surfaces from fouling by bonding antifouling polymers to a susceptible substrate.[33]

Research[]

[]

In 2015, a retrospective analysis comparing the incidence of age-related macular degeneration (AMD) between patients taking versus not taking l-DOPA found that the drug delayed onset of AMD by around 8 years. The authors state that significant effects were obtained for both dry and wet AMD.[34][non-primary source needed]

See also[]

- d-DOPA (Dextrodopa)

- l-DOPS (Droxidopa)

- Methyldopa (Aldomet, Apo-Methyldopa, Dopamet, Novomedopa, etc.)

- Dopamine (Intropan, Inovan, Revivan, Rivimine, Dopastat, Dynatra, etc.)

- Ciladopa

- Neuroleptic malignant syndrome

- Melanin (a metabolite)

References[]

- ^ S. T. Howard, M. B. Hursthouse, C. W. Lehmann, E. A. Poyner (1995). "Experimental and theoretical determination of electronic properties in Ldopa". Acta Crystallogr. B. 51: 328–337. doi:10.1107/S0108768194011407.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Levodopa Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 12 July 2019. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ Lopez VM, Decatur CL, Stamer WD, Lynch RM, McKay BS (September 2008). "L-DOPA is an endogenous ligand for OA1". PLOS Biology. 6 (9): e236. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0060236. PMC 2553842. PMID 18828673.

- ^ Hiroshima Y, Miyamoto H, Nakamura F, Masukawa D, Yamamoto T, Muraoka H, Kamiya M, Yamashita N, Suzuki T, Matsuzaki S, Endo I, Goshima Y (January 2014). "The protein Ocular albinism 1 is the orphan GPCR GPR143 and mediates depressor and bradycardic responses to DOPA in the nucleus tractus solitarii". British Journal of Pharmacology. 171 (2): 403–14. doi:10.1111/bph.12459. PMC 3904260. PMID 24117106.

- ^ Martens, J, Günther, K, Schickedanz M (1986). "Resolution of Optical Isomers by Thin-Layer Chromatography: Enantiomeric Purity of Methyldopa". Arch. Pharm. 319 (6): 572–574. doi:10.1002/ardp.19863190618.

- ^ Hardebo, Jan Erik; Owman, Christer (1980). "Barrier mechanisms for neurotransmitter monoamines and their precursors at the blood-brain interface". Annals of Neurology. 8 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1002/ana.410080102. ISSN 1531-8249. PMID 6105837. S2CID 22874032.

- ^ "Medicare D". Medicare. 2014. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- ^ "Lodosyn", Drugs, nd, retrieved 12 November 2012

- ^ "Inbrija Prescribing Information" (PDF). Retrieved February 14, 2019.

- ^ "Acorda Therapeutics Announces FDA Approval of INBRIJA™ (levodopa inhalation powder)". ir.acorda.com. Retrieved 2019-02-14.

- ^ Scholz H, Trenkwalder C, Kohnen R, Riemann D, Kriston L, Hornyak M (February 2011). Cochrane Movement Disorders Group (ed.). "Levodopa for restless legs syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD005504. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005504.pub2. PMID 21328278.

- ^ Broadley KJ (March 2010). "The vascular effects of trace amines and amphetamines". Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 125 (3): 363–375. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.11.005. PMID 19948186.

- ^ Lindemann L, Hoener MC (May 2005). "A renaissance in trace amines inspired by a novel GPCR family". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 26 (5): 274–281. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.007. PMID 15860375.

- ^ Wang X, Li J, Dong G, Yue J (February 2014). "The endogenous substrates of brain CYP2D". European Journal of Pharmacology. 724: 211–218. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.12.025. PMID 24374199.

- ^ Rodgers, KJ (March 2014). "Non-protein amino acids and neurodegeneration: the enemy within". Experimental Neurology. 253: 192–6. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.12.010. PMID 24374297. S2CID 2288729.

- ^ Hyland K, Clayton PT (December 1992). "Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency: diagnostic methodology" (PDF). Clinical Chemistry. 38 (12): 2405–10. doi:10.1093/clinchem/38.12.2405. PMID 1281049. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-07. Retrieved 2008-10-16.

- ^ Ito S, Kato T, Shinpo K, Fujita K (September 1984). "Oxidation of tyrosine residues in proteins by tyrosinase. Formation of protein-bonded 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine and 5-S-cysteinyl-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine". The Biochemical Journal. 222 (2): 407–11. doi:10.1042/bj2220407. PMC 1144193. PMID 6433900.

- ^ Merims D, Giladi N (2008). "Dopamine dysregulation syndrome, addiction and behavioral changes in Parkinson's disease". Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. 14 (4): 273–80. doi:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2007.09.007. PMID 17988927.

- ^ Dorszewska J, Prendecki M, Lianeri M, Kozubski W (February 2014). "Molecular Effects of L-dopa Therapy in Parkinson's Disease". Current Genomics. 15 (1): 11–7. doi:10.2174/1389202914666131210213042. PMC 3958954. PMID 24653659.

- ^ Ehringer H, Hornykiewicz O (December 1960). "[Distribution of noradrenaline and dopamine (3-hydroxytyramine) in the human brain and their behavior in diseases of the extrapyramidal system]". Klinische Wochenschrift. 38 (24): 1236–9. doi:10.1007/BF01485901. PMID 13726012. S2CID 32896604.

- ^ Birkmayer W, Hornykiewicz O (November 1961). "[The L-3,4-dioxyphenylalanine (DOPA)-effect in Parkinson-akinesia]". Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift. 73: 787–8. PMID 13869404.

- ^ Cotzias GC, Papavasiliou PS, Gellene R (July 1969). "L-dopa in parkinson's syndrome". The New England Journal of Medicine. 281 (5): 272. doi:10.1056/NEJM196907312810518. PMID 5791298.

- ^ Lasker Award 1969 Description, accessed April 1, 2013

- ^ Tanya Simuni and Howard Hurtig. "Levadopa: A Pharmacologic Miracle Four Decades Later", in Parkinson's Disease: Diagnosis and Clinical Management (Google eBook). Eds. Stewart A Factor and William J Weiner. Demos Medical Publishing, 2008

- ^ New England Journal of Medicine [1968] 278 (11) : 630 (Cotzias, G) "L-Dopa for Parkinsonism"

- ^ Knowles WS (1983). "Asymmetric hydrogenation". Accounts of Chemical Research. 16 (3): 106–112. doi:10.1021/ar00087a006.

- ^ "Synthetic scheme for total synthesis of DOPA, L- (Monsanto)". UW Madison, Department of Chemistry. Retrieved Sep 30, 2013.

- ^ Knowles WS (March 1986). "Application of organometallic catalysis to the commercial production of L-DOPA". Journal of Chemical Education. 63 (3): 222. Bibcode:1986JChEd..63..222K. doi:10.1021/ed063p222.

- ^ Pankaj Oudhia. "Kapikachu or Cowhage". Retrieved Nov 3, 2013.

- ^ Ingle PK (May–June 2003). "L-DOPA bearing plants". Natural Product Radiance. 2 (3): 126–133.

- ^ Waite JH, Andersen NH, Jewhurst S, Sun C (2005). "Mussel Adhesion: Finding the Tricks Worth Mimicking". J Adhesion. 81 (3–4): 1–21. doi:10.1080/00218460590944602. S2CID 136967853.

- ^ "Study Reveals Details Of Mussels' Tenacious Bonds". Science Daily. Aug 16, 2006. Retrieved Sep 30, 2013.

- ^ Mussel Adhesive Protein Mimetics Archived 2006-05-29 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Brilliant MH, Vaziri K, Connor TB, Schwartz SG, Carroll JJ, McCarty CA, Schrodi SJ, Hebbring SJ, Kishor KS, Flynn HW, Moshfeghi AA, Moshfeghi DM, Fini ME, McKay BS (March 2016). "Mining Retrospective Data for Virtual Prospective Drug Repurposing: L-DOPA and Age-related Macular Degeneration". The American Journal of Medicine. 129 (3): 292–8. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.10.015. PMC 4841631. PMID 26524704.

External links[]

- "Levodopa". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Aromatic amino acids

- Antiparkinsonian agents

- Carbonic anhydrase activators

- Catecholamines

- Prodrugs