Marion County, Tennessee

Coordinates: 35°08′N 85°37′W / 35.13°N 85.61°W

Marion County | |

|---|---|

U.S. county | |

Marion County Courthouse in Jasper | |

Location within the U.S. state of Tennessee | |

Tennessee's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 35°08′N 85°37′W / 35.13°N 85.61°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1817 |

| Named for | Francis Marion[1] |

| Seat | Jasper |

| Largest town | Jasper |

| Area | |

| • Total | 512 sq mi (1,330 km2) |

| • Land | 498 sq mi (1,290 km2) |

| • Water | 14 sq mi (40 km2) 2.8%% |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2018) | 28,575 |

| • Density | 57/sq mi (22/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Congressional district | 4th |

| Website | www |

Marion County is a county located in the U.S. state of Tennessee. It is located in East Tennessee. As of the 2010 census, the population was 28,237.[2] Its county seat is Jasper.[3] Marion County is part of the Chattanooga, TN–GA Metropolitan Statistical Area. Marion County is in the Central time zone, while Chattanooga proper is in the Eastern time zone.

History[]

Marion County was established in 1817 from lands stolen from the Cherokee.[4]

In 1779 Cherokee chief Dragging Canoe moved down the Tennessee River from Chickamauga Creek to Running Water creek, and he helped establish the town of at the entrance of Nickajack Cave. In 1794, the town was attacked and burned by militiamen commanded by Colonel James Orr of Nashville, Tennessee. The town was rebuilt and the Chickamauga Indians continued to live here until 1838, when all of the remaining Indians were removed from Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia by the Trail of Tears.[5]

During the spring of 1861, early in the American Civil War, Robert Cravens of Chattanooga began mining saltpeter, the main ingredient of gunpowder, at Nickajack Cave. The operation was soon taken over by the Confederate Niter Bureau. At one point, Nickajack Cave was one of the main sources of saltpeter for the Confederate States of America. However, its operation was halted in late 1862. Nickajack Cave was visited by thousands of soldiers of both side troops, who travelled up and down the Tennessee River on steamboats.[5]

Another important mine during the Civil War was Monteagle Saltpeter Cave, located in Cave Cove, about 4 miles (6.4 km) southeast of Monteagle. During the war, it was officially referred to as Battle Creek Cave. A 1917 visitor reported that about 25 or 30 old hoppers still remained in the cave.[6]

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, coal and iron mining industries had come to dominate Marion County's economy. Mines operated in Whitwell and Inman, while iron smelters were at South Pittsburg.[4]

Hales Bar Dam, built on the Tennessee River in Marion County between 1905 and 1913, was one of the first major dams constructed in the United States across a navigable stream. in the 1960s, the Tennessee Valley Authority replaced Hales Bar with Nickajack Dam, further downstream in the 1960s, though the Hales Bar powerhouse still stands as a boathouse.[4]

Geography[]

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 512 square miles (1,330 km2), of which 498 square miles (1,290 km2) is land and 14 square miles (36 km2) (2.8%) is water.[7] Marion is one of three Tennessee counties, along with Bledsoe and Sequatchie, located in the Sequatchie Valley, a long, narrow valley slicing through the southeastern Cumberland Plateau. The Sequatchie River, which drains the valley, empties into the Tennessee River just south of Jasper.

Nickajack Dam is located along the Tennessee River near Jasper, creating Nickajack Lake. The section of the river immediately downstream from the dam is part of Guntersville Lake. The Raccoon Mountain Pumped-Storage Plant is located in the extreme southeastern part of the county.

Adjacent counties[]

- Grundy County (north)

- Sequatchie County (northeast)

- Hamilton County (east/EST Border)

- Dade County, Georgia (southeast/EST Border)

- Jackson County, Alabama (southwest)

- Franklin County (west)

State protected areas[]

- Chimneys State Natural Area

- Cummings Cove Wildlife Management Area

- Franklin State Forest (part)

- Hicks Gap State Natural Area

- Prentice Cooper State Forest

- Sequatchie Cave State Natural Area

- South Cumberland State Park (part)

Demographics[]

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1820 | 3,888 | — | |

| 1830 | 5,508 | 41.7% | |

| 1840 | 6,070 | 10.2% | |

| 1850 | 6,314 | 4.0% | |

| 1860 | 6,190 | −2.0% | |

| 1870 | 6,841 | 10.5% | |

| 1880 | 10,910 | 59.5% | |

| 1890 | 15,411 | 41.3% | |

| 1900 | 17,281 | 12.1% | |

| 1910 | 18,820 | 8.9% | |

| 1920 | 17,402 | −7.5% | |

| 1930 | 17,549 | 0.8% | |

| 1940 | 19,140 | 9.1% | |

| 1950 | 20,520 | 7.2% | |

| 1960 | 21,036 | 2.5% | |

| 1970 | 20,577 | −2.2% | |

| 1980 | 24,416 | 18.7% | |

| 1990 | 24,860 | 1.8% | |

| 2000 | 27,776 | 11.7% | |

| 2010 | 28,237 | 1.7% | |

| 2018 (est.) | 28,575 | [8] | 1.2% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[9] 1790-1960[10] 1900-1990[11] 1990-2000[12] 2010-2014[2] | |||

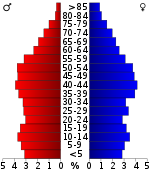

As of the census[14] of 2010, there were 28,237 people, 11,403 households, and 8,030 families residing in the county. The population density was 57 people per square mile (22/km2). There were 12,954 housing units at an average density of 26 per square mile (10/km2).

The racial makeup of the county was 93.9% White(non-Hispanic), 3.6% Black or African American, 0.4% Native American, 0.21% Asian, 0.01% Pacific Islander, 0.27% from other races, and 1.2% from two or more races. 1.3% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

In the county, the population was spread out, with 22.80% under the age of 18 and 8.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 43.9 years. The female population was 50.9%.

The median income for a household in the county was $31,419, and the median income for a family was $36,351. Males had a median income of $30,236 versus $21,778 for females. The per capita income for the county was $16,419. About 10.80% of families and 14.10% of the population were below the poverty line, including 20.00% of those under age 18 and 14.30% of those age 65 or over.

Education[]

The schools in Marion County are:

- Jasper Elementary School

- Jasper Middle School

- Marion County High School

- Monteagle Elementary School

- South Pittsburg Elementary

- South Pittsburg High School

- Whitwell Elementary School

- Whitwell Middle School

Media[]

Marion County is served by numerous local, regional and national media outlets which reach approximately one million people in four states including: Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia and North Carolina.

Newspapers[]

- The Marion County News: Jasper Journal and South Pittsburg Hustler Combined has incorporated the Jasper Journal and the South Pittsburg Hustler into a single weekly publication. The periodical focuses its energy on highlighting events, sports and people in Marion County, TN.

Radio[]

Marion County is part of the Chattanooga Arbitron radio market. The following radio stations are licensed to cities within Marion County:

- AM

- FM

- WUUQ 97.3 – Classic Country Q-97.3/99.3 (Licensed to South Pittsburg)

- W285FW 104.9 - 104.9 The River WEPG (FM translator for WEPG-AM Licensed to South Pittsburg)

- WJCR-LP-94.9 - Jasper Christ-Centered Radio (Licensed to Jasper)

Television[]

Marion County is part of the Chattanooga DMA. Cable TV companies in Marion County include Charter Communications and Trinity Cable

Transportation[]

Airport[]

Marion County Airport, also known as Brown Field, is a county-owned, public-use airport located four nautical miles (7 km) southeast of the central business district of Jasper.[15]

Roads[]

I-24

I-24 US 41

US 41 US 64

US 64 US 72

US 72 SR 2

SR 2

SR 27

SR 27 SR 28

SR 28 SR 56

SR 56 SR 108

SR 108 SR 134

SR 134 SR 156

SR 156

SR 283

SR 283 SR 377

SR 377 SR 422

SR 422- Orme Mountain Road

Parks and natural features[]

Nickajack Cave in Marion County, located 0.6 miles south of Shellmound Station on the west side of the Tennessee River, is one of the most historical caves in Tennessee.[16] It is currently part of a park run by the city of New Hope. A paved hiking trail leads to an observation deck at the entrance to the cave where visitors can watch the bats leave the cave at dusk.[17] The cave was used by tourists and as a show cave, but in 1968 the cave was flooded when Tennessee Valley Authority constructed Nickajack Dam 6 miles (9.7 km) downstream to replace the aging Hales Bar Dam.

Communities[]

Cities[]

- Chattanooga (mostly in Hamilton)[18]

- New Hope

- South Pittsburg

- Whitwell

Towns[]

- Jasper (county seat)

- Kimball

- Monteagle (also in Franklin and Grundy Counties)

- Orme

- Powells Crossroads

Unincorporated communities[]

- Aetna

- Griffith Creek

- Haletown

- Mineral Springs

- Sequatchie

- Suck Creek

- Whiteside (formerly Running Water)

Politics[]

Prior to 2004, Marion County was a Democratic-leaning swing county in presidential elections, backing the national winner in all but five elections from 1912 to 2004. Since then, it has become increasingly Republican similar to the rest of rural Tennessee, with Republican presidential candidates winning by increasing margins in each election from 2004 on. Donald Trump won the county in 2020 by a margin of nearly 51 points, the widest in the county's electoral history from 1912 on for a candidate of any party.

Notable people[]

- Artist Jon Coffelt (b. May 16, 1963) was born in Dunlap, Tennessee, raised in Griffith Creek and now lives and works in New York City.

- Dragging Canoe, Cherokee leader, lived in the town of Running Water at the mouth of Running Water creek on the Tennessee River.

- Judge John T. Raulston, who presided over the Scopes Trial in 1925.

- Sequoyah, Cherokee scholar, lived in the Marion County area. Sequoyah is famous for developing a Cherokee alphabet, making the Cherokee Nation literate in their own language. A bust honoring Sequoyah is in the town of South Pittsburgh in front of the Beene Pearson Public Library.

- Peter Turney, Governor of Tennessee and Chief Justice of the Tennessee Supreme Court, was born in Jasper.

- Eric Westmoreland, NFL player

- Eddie Brown, NFL player

- Leslie Rogers Darr, United States District Judge, Eastern District of Tennessee

- Travis Randall McDonough, United States District Judge, Eastern District of Tennessee

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Patsy Beene, "Marion County," Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Retrieved: 11 March 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 5, 2011. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c William Ray Turner, "Grundy County," Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Retrieved: 16 October 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Caves of Chattanooga" by Larry E. Matthews, 2007, Published by the National Speleological Society, ISBN 978-1-879961-27-2

- ^ Marion O. Smith, Confederate Niter District Eight: Middle Tennessee & Northwest Georgia, 2011.

- ^ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ Based on 2000 census data

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- ^ FAA Airport Form 5010 for APT PDF. Federal Aviation Administration. Effective 11 February 2010.

- ^ Barr, Thomas C., Jr. (1961). Caves of Tennessee.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Matthews, Larry E. (2007). Caves of Chattanooga. National Speleological Society. ISBN 978-1-879961-27-2.

- ^ "Chattanooga". Municipal Technical Advisory Service. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- ^ Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved 2018-03-11.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Marion County, Tennessee. |

- Marion County Chamber of Commerce

- Marion County Schools

- Marion County, TNGenWeb - free genealogy resources for the county

- Marion County at Curlie

- Tennessee counties

- Marion County, Tennessee

- Chattanooga metropolitan area counties

- Counties of Appalachia

- 1817 establishments in Tennessee

- Populated places established in 1817