Memantine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Axura, Ebixa, Namenda, others[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a604006 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ~100% |

| Metabolism | Liver (<10%) |

| Elimination half-life | 60–100 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

show

IUPAC name | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.217.937 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

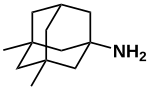

| Formula | C12H21N |

| Molar mass | 179.307 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

show

SMILES | |

show

InChI | |

Memantine is a medication used to slow the progression of moderate-to-severe Alzheimer's disease.[2][3] It is taken by mouth.[2]

Common side effects include headache, constipation, sleepiness, and dizziness.[2][3] Severe side effects may include blood clots, psychosis, and heart failure.[3] It is believed to work by blocking NMDA receptors.[2]

Memantine was approved for medical use in the United States in 2003.[2] It is available as a generic medication.[3] In 2018, it was the 190th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 3 million prescriptions.[4][5]

Medical use[]

Alzheimer's disease and dementia[]

Memantine is used to treat moderate-to-severe Alzheimer's disease, especially for people who are intolerant of or have a contraindication to AChE (acetylcholinesterase) inhibitors.[6][7] One guideline recommends memantine or an AChE inhibitor be considered in people in the early-to-mid stage of dementia.[8]

Memantine has been associated with a modest improvement;[9] with small positive effects on cognition, mood, behavior, and the ability to perform daily activities in moderate-to-severe Alzheimer's disease.[10][11] There does not appear to be any benefit in mild disease.[12]

Memantine when added to donepezil in those with moderate-to-severe dementia resulted in "limited improvements" in a 2017 review.[13] The UK National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) issued guidance in 2018 recommending consideration of the combination of memantine with donepezil in those with moderate-to-severe dementia.[14]

Psychiatry[]

Bipolar disorder[]

Memantine has been investigated as a possible augmentation strategy for depression in bipolar disorder but meta-analytic evidence does not support its clinical utility.[15]

Autism[]

Effects in autism are unclear.[16][17]

Adverse effects[]

Memantine is, in general, well tolerated.[9] Common adverse drug reactions (≥1% of people) include confusion, dizziness, drowsiness, headache, insomnia, agitation, and/or hallucinations. Less common adverse effects include vomiting, anxiety, hypertonia, cystitis, and increased libido.[9][18]

Like many other NMDA antagonists, memantine behaves as a dissociative anesthetic at supratherapeutic doses.[19] Despite isolated reports, recreational use of memantine is rare due to the drug's long duration and limited availability.[19] Also memantine seems to lack effects such as euphoria or hallucinations.[20]

Memantine appears to be generally well tolerated by children with autism spectrum disorder.[21]

Pharmacology[]

Glutamate[]

A dysfunction of glutamatergic neurotransmission, manifested as neuronal excitotoxicity, is hypothesized to be involved in the etiology of Alzheimer's disease. Targeting the glutamatergic system, specifically NMDA receptors, offers a novel approach to treatment in view of the limited efficacy of existing drugs targeting the cholinergic system.[22]

Memantine is a low-affinity voltage-dependent uncompetitive antagonist at glutamatergic NMDA receptors.[23][24] By binding to the NMDA receptor with a higher affinity than Mg2+ ions, memantine is able to inhibit the prolonged influx of Ca2+ ions, particularly from extrasynaptic receptors, which forms the basis of neuronal excitotoxicity. The low affinity, uncompetitive nature, and rapid off-rate kinetics of memantine at the level of the NMDA receptor-channel, however, preserves the function of the receptor at synapses, as it can still be activated by physiological release of glutamate following depolarization of the postsynaptic neuron.[25][26][27] The interaction of memantine with NMDA receptors plays a major role in the symptomatic improvement that the drug produces in Alzheimer's disease. However, there is no evidence as yet that the ability of memantine to protect against NMDA receptor-mediated excitotoxicity has a disease-modifying effect in Alzheimer's, although this has been suggested in animal models.[26]

Memantine's antagonism on NMDA receptors has aroused interest in repurposing it for mental illnesses such as bipolar disorder,[15] considering the involvement of the glutamatergic system in the pathophysiology of mood disorders.[28]

Serotonin[]

Memantine acts as a non-competitive antagonist at the 5-HT3 receptor, with a potency similar to that for the NMDA receptor.[29] Many 5-HT3 antagonists function as antiemetics, however the clinical significance of this serotonergic activity in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease is unknown.

Cholinergic[]

Memantine acts as a non-competitive antagonist at different neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) at potencies possibly similar to the NMDA and 5-HT3 receptors, but this is difficult to ascertain with accuracy because of the rapid desensitization of nAChR responses in these experiments. It can be noted that memantine is an antagonist at Alpha-7 nAChR, which may contribute to initial worsening of cognitive function during early memantine treatment. Alpha-7 nAChR upregulates quickly in response to antagonism, which could explain the cognitive-enhancing effects of chronic memantine treatment.[30][31] It has been shown that the number of nicotinic receptors in the brain are reduced in Alzheimer's disease, even in the absence of a general decrease in the number of neurons, and nicotinic receptor agonists are viewed as interesting targets for anti-Alzheimer drugs.[32]

Dopamine[]

Memantine acts as an agonist at the dopamine D2 receptor with equal or slightly higher affinity than to the NMDA receptors.[33]

Sigmaergic[]

Memantine acts as an agonist at the σ1 receptor with a low affinity (Ki 2.6 μM).[34] The consequences of this activity are unclear (as the role of sigma receptors in general is not yet that well understood). Due to this low affinity, therapeutic concentrations of memantine are most likely too low to have any sigmaergic effect as a typical therapeutic dose is 20 mg, however excessive doses of memantine taken for recreational purposes many times greater than prescribed doses may indeed activate this receptor.[35]

Research[]

Psychiatry[]

Memantine, in light of its NMDA receptor antagonism, has been repurposed as a possible adjunctive treatment for depressive episodes in subjects with bipolar disorder, considering the involvement of the glutamatergic system in the pathophysiology of bipolar illness.[28] However, evidence from meta-analyses showed that memantine was not significantly superior to placebo for bipolar depression.[15]

History[]

Memantine was first synthesized and patented by Eli Lilly and Company in 1968 as an anti-diabetic agent, but it was ineffective at lowering blood sugar. Later it was discovered to have CNS activity, and was developed by Merz for dementia in Germany; the NMDA activity was discovered after trials had already begun. Memantine was first marketed for dementia in Germany in 1989 under the name Axura.[36]

In the US, some CNS activities were discovered at Children's Hospital of Boston in 1990, and Children's licensed patents covering uses of memantine outside the field of ophthalmology to Neurobiological Technologies (NTI) in 1995.[37] In 1998 NTI amended its agreement with Children's to allow Merz to take over development.[38]

In 2000, Merz partnered with Forest to develop the drug for Alzheimer's disease in the U.S. under the name Namenda.[36]

In 2000, Merz partnered with Suntory for the Japanese market and with Lundbeck for other markets including Europe;[39] the drug was originally marketed by Lundbeck under the name Ebixa.[36]

Sales of the drug reached $1.8 billion for 2014.[40] The cost of Namenda was $269 to $489 a month in 2012.[41]

In February 2014, as the July 2015 patent expiration for memantine neared, Actavis, which had acquired Forest, announced that it was launching an extended release (XR) form of memantine that could be taken once a day instead of twice a day as needed with the then-current "immediate release" (IR) version, and that it intended to stop selling the IR version in August 2014 and withdraw the marketing authorization. This is a tactic to thwart generic competition called "". However the supply of the XR version ran short, so Actavis extended the deadline until the fall. In September 2014 the attorney general of New York, Eric Schneiderman, filed a lawsuit to compel Actavis to keep selling the IR version on the basis of antitrust law.[42][43]

In December 2014, a judge granted New York State its request and issued an injunction, preventing Actavis from withdrawing the IR version until generic versions could launch. Actavis appealed and in May a panel of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the injunction, and in June Actavis asked that its case be heard by the full Second Circuit panel.[44][45] In August 2015, Actavis' request was denied.[46]

Society and culture[]

Recreational use[]

One preclinical study on monkeys showed that memantine was capable of inducing a PCP-like intoxication.[47] Because of its very long biological half-life, memantine was previously thought not to be a drug of abuse, although a few cases of sporadic recreational use have been described.[48]

A study examining self-reported misuse of memantine on the social network Reddit shown that the drug was used as a recreational drug and as a nootropic, but also that it was misused in various illnesses as self-medication without strong scientific basis.[49]

Brand names[]

As of August 2017, memantine was marketed under many brand names worldwide including Abixa, Adaxor, Admed, Akatinol, Alceba, Alios, Almenta, Alois, Alzant, Alzer, Alzia, Alzinex, Alzixa, Alzmenda, Alzmex, Axura, Biomentin, Carrier, Cogito, Cognomem, Conexine, Cordure, Dantex, Demantin, Demax, Dementa, Dementexa, Ebitex, Ebixa, Emantin, Emaxin, Esmirtal, Eutebrol, Evy, Ezemantis, Fentina, Korint, Lemix, Lindex, Lindex, Lucidex, Manotin, Mantine, Mantomed, Marbodin, Mardewel, Marixino, Maruxa, Maxiram, Melanda, Memabix, Memamed, Memando, Memantin, Memantina, Memantine, Mémantine, Memantinol, Memantyn, Memanvitae, Memanxa, Memanzaks, Memary, Memax, Memexa, Memigmin, Memikare, Memogen, Memolan, Memorel, Memorix, Memotec, Memox, Memxa, Mentikline, Mentium, Mentixa, Merandex, Merital, Mexia, Mimetix, Mirvedol, Modualz, Morysa, Namenda, Nemdatine, Nemdatine, Nemedan, Neumantine, Neuro-K, Neuroplus, Noojerone, Polmatine, Prilben, Pronervon, Ravemantine, Talentum, Timantila, Tingreks, Tonibral, Tormoro, Valcoxia, Vilimen, Vivimex, Witgen, Xapimant, Ymana, Zalatine, Zemertinex, Zenmem, Zenmen, and Zimerz.[1]

It was also marketed in some countries as a combination drug with donepezil under the brands Namzaric, Neuroplus Dual, and Tonibral MD.[1]

See also[]

- 3-HO-PCP

- Rhynchophylline

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "International brands for memantine". Drugs.com. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Memantine Hydrochloride Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. pp. 303–304. ISBN 9780857113382.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2021". ClinCalc. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ "Memantine Hydrochloride - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ Mount C, Downton C (July 2006). "Alzheimer disease: progress or profit?". Nature Medicine. 12 (7): 780–4. doi:10.1038/nm0706-780. PMID 16829947.

- ^ NICE review of technology appraisal guidance 111 January 18, 2011 Alzheimer's disease - donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine and memantine (review): final appraisal determination

- ^ Page AT, Potter K, Clifford R, McLachlan AJ, Etherton-Beer C (October 2016). "Medication appropriateness tool for co-morbid health conditions in dementia: consensus recommendations from a multidisciplinary expert panel". Internal Medicine Journal. 46 (10): 1189–1197. doi:10.1111/imj.13215. PMC 5129475. PMID 27527376.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Rossi S, editor. Australian Medicines Handbook 2006. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook; 2006.

- ^ McShane, Rupert; Westby, Maggie J.; Roberts, Emmert; Minakaran, Neda; Schneider, Lon; Farrimond, Lucy E.; Maayan, Nicola; Ware, Jennifer; Debarros, Jean (20 March 2019). "Memantine for dementia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3: CD003154. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003154.pub6. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6425228. PMID 30891742.

- ^ van Dyck CH, Tariot PN, Meyers B, Malca Resnick E (2007). "A 24-week randomized, controlled trial of memantine in patients with moderate-to-severe Alzheimer disease". Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 21 (2): 136–43. doi:10.1097/WAD.0b013e318065c495. PMID 17545739. S2CID 25621202.

- ^ Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Higgins JP, McShane R (August 2011). "Lack of evidence for the efficacy of memantine in mild Alzheimer disease". Archives of Neurology. 68 (8): 991–8. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2011.69. PMID 21482915.

- ^ Chen, Ruey; Chan, Pi-Tuan; Chu, Hsin; Lin, Yu-Cih; Chang, Pi-Chen; Chen, Chien-Yu; Chou, Kuei-Ru (21 August 2017). Chen, Kewei (ed.). "Treatment effects between monotherapy of donepezil versus combination with memantine for Alzheimer disease: A meta-analysis". PLOS ONE. 12 (8): e0183586. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1283586C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0183586. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5565113. PMID 28827830.

- ^ "Overview | Dementia: assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers | Guidance | NICE". www.nice.org.uk. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Bartoli F, Cavaleri D, Bachi B, Moretti F, Riboldi I, Crocamo C, Carrà G (September 2021). "Repurposed drugs as adjunctive treatments for mania and bipolar depression: A meta-review and critical appraisal of meta-analyses of randomized placebo-controlled trials". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 143: 230–238. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.09.018.

- ^ Parr, J (7 January 2010). "Autism". BMJ Clinical Evidence. 2010. PMC 2907623. PMID 21729335.

- ^ Hong, Michael P.; Erickson, Craig A. (3 August 2019). "Investigational drugs in early-stage clinical trials for autism spectrum disorder". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. Informa UK Limited. 28 (8): 709–718. doi:10.1080/13543784.2019.1649656. ISSN 1354-3784. PMID 31352835. S2CID 198967266.

- ^ Joint Formulary Committee (2004). British National Formulary (47th ed.). London: BMA and the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. ISBN 978-0-85369-584-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Morris H, Wallach J (2014). "From PCP to MXE: a comprehensive review of the non-medical use of dissociative drugs". Drug Testing and Analysis. 6 (7–8): 614–32. doi:10.1002/dta.1620. PMID 24678061.

- ^ Swedberg MD, Ellgren M, Raboisson P (April 2014). "mGluR5 antagonist-induced psychoactive properties: MTEP drug discrimination, a pharmacologically selective non-NMDA effect with apparent lack of reinforcing properties". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 349 (1): 155–64. doi:10.1124/jpet.113.211185. PMID 24472725. S2CID 787751.

- ^ Elbe, Dean (2019). Clinical handbook of psychotropic drugs for children and adolescents (Tertiary source). Boston, MA: Hogrefe. pp. 366–369. ISBN 978-1-61676-550-7. OCLC 1063705924.

- ^ Cacabelos R, Takeda M, Winblad B (January 1999). "The glutamatergic system and neurodegeneration in dementia: preventive strategies in Alzheimer's disease". International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 14 (1): 3–47. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199901)14:1<3::AID-GPS897>3.0.CO;2-7. PMID 10029935.

- ^ Rogawski MA, Wenk GL (2003). "The neuropharmacological basis for the use of memantine in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease". CNS Drug Reviews. 9 (3): 275–308. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2003.tb00254.x. PMC 6741669. PMID 14530799.

- ^ Robinson DM, Keating GM (2006). "Memantine: a review of its use in Alzheimer's disease". Drugs. 66 (11): 1515–34. doi:10.2165/00003495-200666110-00015. PMID 16906789.

- ^ Xia P, Chen HS, Zhang D, Lipton SA (August 2010). "Memantine preferentially blocks extrasynaptic over synaptic NMDA receptor currents in hippocampal autapses". The Journal of Neuroscience. 30 (33): 11246–50. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2488-10.2010. PMC 2932667. PMID 20720132.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Parsons CG, Stöffler A, Danysz W (November 2007). "Memantine: a NMDA receptor antagonist that improves memory by restoration of homeostasis in the glutamatergic system--too little activation is bad, too much is even worse". Neuropharmacology. 53 (6): 699–723. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.07.013. PMID 17904591. S2CID 6599658.

- ^ Lipton SA (October 2007). "Pathologically activated therapeutics for neuroprotection". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 8 (10): 803–8. doi:10.1038/nrn2229. PMID 17882256. S2CID 34931289.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bartoli, F; Misiak, B; Callovini, T; Cavaleri, D; Cioni, RM; Crocamo, C; Savitz, JB; Carrà, G (19 October 2020). "The kynurenine pathway in bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis on the peripheral blood levels of tryptophan and related metabolites". Molecular Psychiatry. doi:10.1038/s41380-020-00913-1. PMID 33077852. S2CID 224314102.

- ^ Rammes G, Rupprecht R, Ferrari U, Zieglgänsberger W, Parsons CG (June 2001). "The N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor channel blockers memantine, MRZ 2/579 and other amino-alkyl-cyclohexanes antagonise 5-HT(3) receptor currents in cultured HEK-293 and N1E-115 cell systems in a non-competitive manner". Neuroscience Letters. 306 (1–2): 81–4. doi:10.1016/S0304-3940(01)01872-9. PMID 11403963. S2CID 9655208.

- ^ Buisson B, Bertrand D (March 1998). "Open-channel blockers at the human alpha4beta2 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor". Molecular Pharmacology. 53 (3): 555–63. doi:10.1124/mol.53.3.555. PMID 9495824. S2CID 5865674.

- ^ Aracava Y, Pereira EF, Maelicke A, Albuquerque EX (March 2005). "Memantine blocks alpha7* nicotinic acetylcholine receptors more potently than n-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in rat hippocampal neurons". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 312 (3): 1195–205. doi:10.1124/jpet.104.077172. PMID 15522999. S2CID 17585264.

- ^ Gotti C, Clementi F (December 2004). "Neuronal nicotinic receptors: from structure to pathology". Progress in Neurobiology. 74 (6): 363–96. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.09.006. PMID 15649582. S2CID 24093369.

- ^ Seeman P, Caruso C, Lasaga M (February 2008). "Memantine agonist action at dopamine D2High receptors". Synapse. 62 (2): 149–53. doi:10.1002/syn.20472. PMID 18000814. S2CID 20494427.

- ^ Peeters M, Romieu P, Maurice T, Su TP, Maloteaux JM, Hermans E (April 2004). "Involvement of the sigma 1 receptor in the modulation of dopaminergic transmission by amantadine". The European Journal of Neuroscience. 19 (8): 2212–20. doi:10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03297.x. PMID 15090047. S2CID 19479968.

- ^ "Pharms - Memantine (also Namenda) : Erowid Exp: Main Index". erowid.org. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Witt A, Macdonald N, Kirkpatrick P (February 2004). "Memantine hydrochloride". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 3 (2): 109–10. doi:10.1038/nrd1311. PMID 15040575. S2CID 2258982.

- ^ "Form 10-KSB For the fiscal year ended June 30, 1996". SEC Edgar. 30 September 1996. NTI-Children's license is included in the filing.

- ^ Delevett P (9 January 2000). "Cash is king, focus is queen". Silicon Valley Business Journal.

- ^ Staff (15 August 2000). "Lundbeck signs memantine licensing agreement for Merz+Co". The Pharma Letter.

- ^ "Namenda Sales Data". Drugs.com. February 2014.

- ^ "Evaluating Prescription Drugs Used to Treat: Alzheimer's Disease. Comparing Effectiveness, Safety, and Price" (PDF). Consumer Reports Health. May 2012.

- ^ Pollack A (15 September 2014). "Forest Laboratories' Namenda Is Focus of Lawsuit". The New York Times.

- ^ Capati VC, Kesselheim AS (April 2016). "Drug Product Life-Cycle Management as Anticompetitive Behavior: The Case of Memantine". Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy. 22 (4): 339–44. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.4.339. PMID 27023687.

- ^ "Actavis Confirms Appeals Court Ruling Requiring Continued Distribution of Namenda IR". Actavis. 22 May 2015.

- ^ Gurrieri V (9 June 2015). "Actavis, Others Plotted To Delay Generic Namenda, Suit Says - Law360". Law360.

- ^ LoBiondo GA (12 August 2015). "Second Circuit Denies Petition for Actavis Rehearing | David Kleban". Patterson Belknap Webb & Tyler LLP.

- ^ Nicholson, K. L.; Jones, H. E.; Balster, R. L. (May 1998). "Evaluation of the reinforcing and discriminative stimulus properties of the low-affinity N-methyl-D-aspartate channel blocker memantine". Behavioural Pharmacology. 9 (3): 231–243. ISSN 0955-8810. PMID 9832937.

- ^ Morris, Hamilton; Wallach, Jason (July 2014). "From PCP to MXE: a comprehensive review of the non-medical use of dissociative drugs: PCP to MXE". Drug Testing and Analysis. 6 (7–8): 614–632. doi:10.1002/dta.1620. PMID 24678061.

- ^ Natter, Johan; Michel, Bruno (2020). "Memantine misuse and social networks: A content analysis of Internet self-reports". Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 29 (9): 1189–1193. doi:10.1002/pds.5070. ISSN 1099-1557. PMID 32602152. S2CID 220270495.

Further reading[]

- Lipton SA (April 2005). "The molecular basis of memantine action in Alzheimer's disease and other neurologic disorders: low-affinity, uncompetitive antagonism". Current Alzheimer Research. 2 (2): 155–65. doi:10.2174/1567205053585846. PMID 15974913.

External links[]

- "Memantine". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Adamantanes

- Antidementia agents

- AbbVie brands

- Antiparkinsonian agents

- Amines

- Dissociative drugs

- NMDA receptor antagonists

- Sigma agonists

- Treatment of Alzheimer's disease