Butane

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Butane[3] | |||

| Systematic IUPAC name

Tetracarbane (never recommended[3]) | |||

| Other names | |||

| Identifiers | |||

CAS Number

|

| ||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

Beilstein Reference

|

969129 | ||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.136 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| E number | E943a (glazing agents, ...) | ||

Gmelin Reference

|

1148 | ||

| KEGG | |||

| MeSH | butane | ||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

| UN number | 1011 | ||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

show

InChI | |||

show

SMILES | |||

| Properties | |||

Chemical formula

|

C4H10 | ||

| Molar mass | 58.124 g·mol−1 | ||

| Appearance | Colorless gas | ||

| Odor | Gasoline-like or natural gas-like[1] | ||

| Density | 2.48 kg/m3 (at 15 °C (59 °F)) | ||

| Melting point | −140 to −134 °C; −220 to −209 °F; 133 to 139 K | ||

| Boiling point | −1 to 1 °C; 30 to 34 °F; 272 to 274 K | ||

Solubility in water

|

61 mg/L (at 20 °C (68 °F)) | ||

| log P | 2.745 | ||

| Vapor pressure | ~170 kPa at 283 K [4] | ||

Henry's law

constant (kH) |

11 nmol Pa−1 kg−1 | ||

| Conjugate acid | Butanium | ||

Magnetic susceptibility (χ)

|

−57.4·10−6 cm3/mol | ||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Heat capacity (C)

|

98.49 J/(K·mol) | ||

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−126.3–−124.9 kJ/mol | ||

Std enthalpy of

combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

−2.8781–−2.8769 MJ/mol | ||

| Hazards[5] | |||

| Safety data sheet | See: data page | ||

| GHS pictograms |

| ||

| GHS Signal word | Danger | ||

GHS hazard statements

|

H220 | ||

GHS precautionary statements

|

P210 | ||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

1

4

0 SA | ||

| Flash point | −60 °C (−76 °F; 213 K) | ||

Autoignition

temperature |

405 °C (761 °F; 678 K) | ||

| Explosive limits | 1.8–8.4% | ||

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |||

PEL (Permissible)

|

none[1] | ||

REL (Recommended)

|

TWA 800 ppm (1900 mg/m3)[1] | ||

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

1600 ppm[1] | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Related alkanes

|

| ||

Related compounds

|

Perfluorobutane | ||

| Supplementary data page | |||

Structure and

properties |

Refractive index (n), Dielectric constant (εr), etc. | ||

Thermodynamic

data |

Phase behaviour solid–liquid–gas | ||

Spectral data

|

UV, IR, NMR, MS | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

Butane (/ˈbjuːteɪn/) or n-butane is an alkane with the formula C4H10. Butane is a gas at room temperature and atmospheric pressure. Butane is a highly flammable, colorless, easily liquefied gas that quickly vaporizes at room temperature. The name butane comes from the roots but- (from butyric acid, named after the Greek word for butter) and -ane. It was discovered by the chemist Edward Frankland in 1849.[6] It was found dissolved in crude petroleum in 1864 by Edmund Ronalds, who was the first to describe its properties.[7][8]

History[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (June 2021) |

Butane was discovered by the chemist Edward Frankland in 1849. It was found dissolved in crude petroleum in 1864 by Edmund Ronalds, who was the first to describe its properties.

Isomers[]

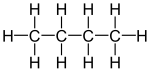

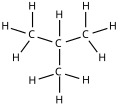

| Common name | normal butane unbranched butane n-butane |

isobutane i-butane |

| IUPAC name | butane | methylpropane |

| Molecular diagram |

|

|

| Skeletal diagram |

|

Rotation about the central C−C bond produces two different conformations (trans and gauche) for n-butane.[9]

Reactions[]

When oxygen is plentiful, butane burns to form carbon dioxide and water vapor; when oxygen is limited, carbon (soot) or carbon monoxide may also be formed. Butane is denser than air.

When there is sufficient oxygen:

- 2 C4H10 + 13 O2 → 8 CO2 + 10 H2O

When oxygen is limited:

- 2 C4H10 + 9 O2 → 8 CO + 10 H2O

By weight, butane contains about 49.5 MJ/kg (13.8 kWh/kg; 22.5 MJ/lb; 21,300 Btu/lb) or by liquid volume 29.7 megajoules per liter (8.3 kWh/l; 112 MJ/U.S. gal; 107,000 Btu/U.S. gal).

The maximum adiabatic flame temperature of butane with air is 2,243 K (1,970 °C; 3,578 °F).

n-Butane is the feedstock for DuPont's catalytic process for the preparation of maleic anhydride:

- 2 CH3CH2CH2CH3 + 7 O2 → 2 C2H2(CO)2O + 8 H2O

n-Butane, like all hydrocarbons, undergoes free radical chlorination providing both 1-chloro- and 2-chlorobutanes, as well as more highly chlorinated derivatives. The relative rates of the chlorination is partially explained by the differing bond dissociation energies, 425 and 411 kJ/mol for the two types of C-H bonds.

Uses[]

Normal butane can be used for gasoline blending, as a fuel gas, fragrance extraction solvent, either alone or in a mixture with propane, and as a feedstock for the manufacture of ethylene and butadiene, a key ingredient of synthetic rubber. Isobutane is primarily used by refineries to enhance (increase) the octane number of motor gasoline.[10][11][12][13]

When blended with propane and other hydrocarbons, it may be referred to commercially as LPG, for liquefied petroleum gas. It is used as a petrol component, as a feedstock for the production of base petrochemicals in steam cracking, as fuel for cigarette lighters and as a propellant in aerosol sprays such as deodorants.[14]

Very pure forms of butane, especially isobutane, can be used as refrigerants and have largely replaced the ozone-layer-depleting halomethanes, for instance in household refrigerators and freezers. The system operating pressure for butane is lower than for the halomethanes, such as R-12, so R-12 systems such as in automotive air conditioning systems, when converted to pure butane will not function optimally and therefore a mix of isobutane and propane is used to give cooling system performance comparable to R-12.

Butane is also used as lighter fuel for a common lighter or butane torch and is sold bottled as a fuel for cooking, barbecues and camping stoves. Butane canisters global market is dominated by South Korean manufacturers.[15]

As fuel, it is often mixed with small amounts of hydrogen sulfide and mercaptans which will give the unburned gas an offensive smell easily detected by the human nose. In this way, butane leaks can easily be identified. While hydrogen sulfide and mercaptans are toxic, they are present in levels so low that suffocation and fire hazard by the butane becomes a concern far before toxicity.[16][17] Most commercially available butane also contains a certain amount of contaminant oil which can be removed through filtration but which will otherwise leave a deposit at the point of ignition and may eventually block the uniform flow of gas.[18] The butane used in fragrance extraction does not contain these contaminants[19] and butane gases can cause gas explosions in poorly ventilated areas if leaks go unnoticed and are ignited by spark or flame.[5]Butane in its purest form is also used as a solvent in the industrial extraction of cannabis oils.

Butane fuel canisters for use in camping stoves

Butane lighter, showing liquid butane reservoir

An aerosol spray can, which may be using butane as a propellant

Butane gas cylinder used for cooking

Effects and health issues[]

Inhalation of butane can cause euphoria, drowsiness, unconsciousness, asphyxia, cardiac arrhythmia, fluctuations in blood pressure and temporary memory loss, when abused directly from a highly pressurized container, and can result in death from asphyxiation and ventricular fibrillation. It enters the blood supply and within seconds produces intoxication.[20] Butane is the most commonly abused volatile substance in the UK, and was the cause of 52% of solvent related deaths in 2000.[21] By spraying butane directly into the throat, the jet of fluid can cool rapidly to −20 °C (−4 °F) by expansion, causing prolonged laryngospasm.[22] "Sudden sniffer's death" syndrome, first described by Bass in 1970,[23] is the most common single cause of solvent related death, resulting in 55% of known fatal cases.[22]

See also[]

- Isobutane

- Cyclobutane

- Dimethyl ether

- Volatile substance abuse

- Butane (data page)

- Butanone

- n-Butanol

- Liquefied petroleum gas

- Industrial gas

- Butane torch

- Gas explosions

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0068". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ Hofmann, August Wilhelm Von (1 January 1867). "I. On the action of trichloride of phosphorus on the salts of the aromatic monamines". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 15: 54–62. doi:10.1098/rspl.1866.0018. S2CID 98496840.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Front Matter". Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry : IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. p. 4. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-FP001. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

Similarly, the retained names ‘ethane’, ‘propane’, and ‘butane’ were never replaced by systematic names ‘dicarbane’, ‘tricarbane’, and ‘tetracarbane’ as recommended for analogues of silane, ‘disilane’; phosphane, ‘triphosphane’; and sulfane, ‘tetrasulfane’.

- ^ W. B. Kay (1940). "Pressure-Volume-Temperature Relations for n-Butane". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry. 32 (3): 358–360. doi:10.1021/ie50363a016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Safety Data Sheet, Material Name: N-Butane" (PDF). USA: Matheson Tri-Gas Incorporated. 5 February 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- ^ Russel, Colin A. (20 March 2009). "Frankland – the First Organometallic Chemist" (PDF). The Sixth Wheeler Lecture. Royal Society of Chemistry. Archived from the original on 17 April 2017.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- ^ Watts, H.; Muir, M. M. P.; Morley, H. F. (1894). Watts' Dictionary of Chemistry. Watts' Dictionary of Chemistry. Longmans, Green. p. 385.

- ^ Maybery, C. F. (1896). "On the Composition of the Ohio and Canadian Sulphur Petroleums". Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 31: 1–66. doi:10.2307/20020618. JSTOR 20020618.

- ^ (2009). "Enthalpy Difference between Conformations of Normal Alkanes: Raman Spectroscopy Study of n-Pentane and n-Butane". J. Phys. Chem. A. 113 (6): 1012–9. doi:10.1021/jp809639s. PMID 19152252.

- ^ MarkWest Energy Partners, L.P. Form 10-K. Sec.gov.

- ^ Copano Energy, L.L.C. Form 10-K. Sec.gov. Retrieved on 2012-12-03.

- ^ Targa Resources Partners LP Form10-k. Sec.gov. Retrieved on 2012-12-03.

- ^ Crosstex Energy, L.P. FORM 10-K. Sec.gov.

- ^ A Primer on Gasoline Blending. An EPRINC Briefing Memorandum.

- ^ "Entrepreneur overcame hardships of Chinese prison". houstonchronicle.com. 21 June 2016. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- ^ Gresham, Chip (16 November 2019). "Hydrogen Sulfide Toxicity: Practice Essentials, Pathophysiology, Etiology". Medscape Reference. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Committee on Acute Exposure Guideline Levels; Committee on Toxicology; Board on Environmental Studies and Toxicology; Division on Earth and Life Studies; National Reserch Council (26 September 2013). 2. Methyl Mercaptan Acute Exposure Guideline Levels. NCBI Bookshelf.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ "BHO Mystery Oil". Skunk Pharm Research. 26 August 2013. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- ^ "Final Report of the Safety Assessment of Isobutane, Isopentane, n-Butane, and Propane". Journal of the American College of Toxicology. SAGE Publications. 1 (4): 127–142. 1982. doi:10.3109/10915818209021266. ISSN 0730-0913. S2CID 208503534.

- ^ "Neurotoxic Effects from Butane Gas". thcfarmer.com. 19 December 2009. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- ^ Field-Smith M., Bland J. M., Taylor J. C. et al. "Trends in death Associated with Abuse of Volatile Substances 1971–2004" (PDF). Department of Public Health Sciences. London: St George’s Medical School. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2007.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ramsey J., Anderson H. R., Bloor K. et al. (1989). "An introduction to the practice, prevalence and chemical toxicology of volatile substance abuse". Hum Toxicol. 8 (4): 261–269. doi:10.1177/096032718900800403. PMID 2777265. S2CID 19617950.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- ^ Bass M. (1970). "Sudden sniffing death". JAMA. 212 (12): 2075–2079. doi:10.1001/jama.1970.03170250031004. PMID 5467774.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Butane. |

- Butane

- Alkanes

- Fuel gas

- Refrigerants

- GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulators

- E-number additives